Workplace drama Severance Season 2 enhances performance by moving sideways from work ethics to reach the complicated hearts of its protagonists.

Severance Dan Erickson Apple TV+ 17 January 2025

Severance Dan Erickson Apple TV+ 17 January 2025

Dropping the most meticulously crafted TV mystery since LOST and disappearing for three years either means you have egomaniacal confidence (and likely production issues), or you have lost the plot. For Severance, AppleTV+’s biggest hit since Ted Lasso, it was production issues. The series needed time to clear the industry strike hurdles (plus time for rewrites and reshoots) since its debut in early 2022.

Over these years of silent mystery about what is happening within Severance‘s Lumon Industries, we wondered where this eerie mind-bender about a dystopian world of downtrodden workers and their abusive, all-powerful overseers might lead. Now that the elevator doors have slid open to Season 2, we still wonder about most of it, but with a refined understanding of this sci-fi show’s meaning.

Mild spoilers for Season 2 follow.

Lumon Industries’ Orientation Booklet

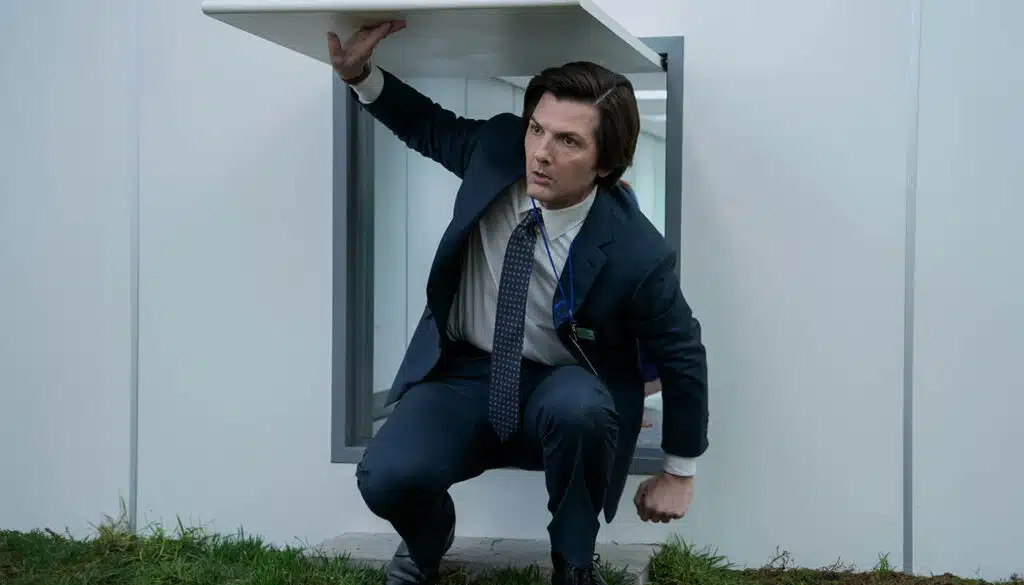

The sophomore season of TV’s most mind-boggling workplace and identity drama, which premiered in January 2025, is considerably more profound, emotionally engaging, and even more aesthetically astonishing (we get to go outside a lot this time!) than its predecessor. While at times overly ambitious in scope – following colossal viewer expectations set up in Season 1 – Severance Season 2 nevertheless successfully oscillates between an office thriller, a psychological horror of the absurd and the uncanny, and affecting (melo)drama.

Refreshingly propulsive toward the finalé and full of surprising developments, Season 2 of Severance sets up the stage immaculately for the hopefully final third season, a nod of respect to its enormously invested audience who deserves better than diluted and inert six-season arcs with minimal payoff. Apple TV+ also finally seems to understand what to do when one of its originals beguiles the masses: knuckle down on the lore.

To promote Severance Season 2, creators set up a glass cubicle in New York’s Central Station, where the main cast acted out their typically dull day at work while the frenzied masses recorded and analyzed their every move. For the role-playing fans, a Lumon Industries game was made available on the App Store, followed by a 39-page self-help book, “The You You Are”, based on the hit bestseller of inane writings by the protagonist’s brother-in-law.

To round up the meme-ification effect, just before the premiere, Apple TV+ partnered with the Sunday Scaries work satire Instagram page and podcast to create an assortment of anti-motivational work memes with Severance characters front and center. All are examples of genius marketing with painfully appropriate symbolism. Yet, as has always been the case with Severance, actually getting to the bottom of things requires laser-sharp attention and a considerable investment beyond social media.

Tackling the immense thematic and storytelling density of the new season without a solid recap of what came before would be a fool’s errand, so I recommend re-watching the older episodes if you are to follow the many purposefully nebulous, seemingly disjointed, and often prolonged plot grafts and cliffhangers. Severance still largely succeeds in being a fascinating watch not just for devotees but casual Joes, too. However, if you blink, you might miss Severance‘s mounting, bifurcating mysteries and schemes. For better or for worse, a consistent high viewer alert is advised.

Staff: A Performance Overview

Created by Dan Erickson and developed, executive produced, and (partially) directed by Ben Stiller, Severance introduced us to Mark S (Adam Scott), Dylan G (Zach Cherry), Helly R (Britt Lower), and Irving B (John Turturro), four small-time clerks spending their lives at the underground office of their employer Lumon Industries, a biotechnology conglomerate. This is meant literally: all four employees have undergone a procedure called “severance”, surgically separating their lives and identities at work from their private lives.

Lumon’s strict control of brain implants ensures that the severed subjects outside of work (“outies”) have no recollection of what their “innies” do at work. Using this method, two entirely separate identities are created, one which continuously experiences their free time while retaining their identity, and the other, stripped of memory, whose entire life is confined to a plain cubicle illuminated by ominous halogen.

Put bluntly, all Mark and his Macrodata Refinement (MDR) team have ever known is typing on computer keyboards and grouping strange sequences of numbers (?!) in a sterile confinement between virtually endless, near-identical hallways. This is all they will ever get from life, which will be extinguished when their outies retire or quit. Whatever personality or experience these innies develop hinges entirely on the will of their outies and their startlingly controlling Lumon supervisors, notably their quirky floor supervisor Seth Milchick (a breakout Tramell Tillman) and the ruthless severed floor manager Harmony Cobel (a chilly Patricia Arquette).

All four of the MDR staff are kind, warm personalities with only modest dreams and minuscule expectations, but it is evident early on that, apart from occasional (and frankly terrorizing) performative “rewards” for a job well done, these useful sacks of meat have absolutely nothing to look forward to, ever. Stiller, Erickson, and Scott infuse many scenes with amusing bits of slapstick or the comedy of the absurd, but overall, there’s not a trace of joy anywhere in Severance.

Plot developments, which in Season 1 dominantly occur in the sequestered confines of the severed floor, revolve heavily around Lumon Industries’ mythology and operational practices. Kier Eagan (Mark Geller), who founded Lumon Industries in 1865, is posthumously worshipped as a deity: statues and paintings of him adorn Lumon premises, his quotes and “teachings” echo around the offices, even the Lumon HQ town bears his name. Everything Lumon employees do seems to be for the benefit of the cult of Keir, who is referred to exclusively as the supreme arbiter of morality and honor.

On the other hand, despite Lumon’s all-devouring corporatism, severance is considered a hugely controversial procedure by the public. Those who subject themselves to it are often shunned or despised by society at large, deemed either too selfish or too weak to endure life itself (more on that in Season 2).

Expectation Management

As if this setup isn’t instantaneously disconcerting, the lives of the outies are even more disturbing, their decision to sever often guided by trauma or fear. Mark Scout is a widower who created an innie to cut his agonizing days of mourning short. Irving Bailiff is a former US Navy loner who spends his time painting identical images of a dark corridor with an elevator only going down.

In the outstanding finalé of Season 1, “The We We Are”, the innies break through Lumon’s security and “awaken” themselves in the outer world, complicating the neat separation of narratives. We find out that the rebellious, vivacious Helly R is, in fact, Helena Eagan, the callous scion of Lumon, that Irving’s innie’s love interest, Burt (the indomitable Christopher Walken), is happily married on the outside, and that Mark’s presumed dead wife, Gemma (Dichen Lachman), is actually alive and trapped on Lumon premises, working as his wellness counselor “Ms. Casey”. Cobel is not only suspended for “mismanaging” the unacceptably self-determined MDR team but also for posing as Mark’s neighbor, “Mrs. Selvig”, on the outside, observing his routines closely for reasons beyond our comprehension.

This unbearable distrust and tension between the time-looping innies and their masters (“bosses” is simply not accurate enough) can only escalate, which is exactly what happens throughout Severance Season 2. The attention pivots to the outies, whom we get to know intimately, and their relationship to their severed and essentially imprisoned other (innie) selves. Trust is manipulated, and allegiances are formed as these split subjects scuttle to understand what is happening to them both inside and out and if whatever Lumon Industries’ is making – or making happen – can be stopped.

Achievement Overview

In short, the pot boils and then overflows in Season 2. The matters of individual vs. collective identity, perils of self-determination vs. the comfort of obedience, and especially the matters of subjective will and agency vs. the purpose others have carved out for us, multiply manifold. These factors season the melting pot of the uncanny that Severance brews with its original themes of isolation (alienation), corporate abuse of labor(ers), and surveillance.

Vast distances are crossed (literally) and plenty is revealed between the befuddling opener “Hello, Mrs. Cobel” and the nail-biting finalé, “Cold Harbor”, though Erickson and co. frustratingly keep us at arm’s length from the show’s central questions. If anything, the last few scenes promise a bombastic, all-in Season 3. At least we find out, kind of, what the hell Lumon needs all those baby goats for.

The impressively tense direction by Stiller and co. and hugely assured performances by the entire ensemble, with Tillman as a kinetic, simmering standout, mesh well with Erickson’s skillful storytelling dynamic to gloss over some repetitive, drawn out, or logic-defying elements of the eventual big reveal. Seeing how the truths of Lumon’s mission and the severance procedure evade us, not every aspect of the big puzzle(s) compels enough to sustain interest, and a few threaten to drag the narrative sideways.

Still, the poignant new storylines and cleverly ramped-up tension between Severence‘s innies and the outies bring relevant insights into light, often culminating in excellent television. Cue strange multiple love triangles (!), various types of escaping or disappearing, a new puzzle box Lumon Industries outpost, and many “what the???” moments.

Staff Efficiency and Time Management

When the innies “break out” into their outies’ consciousness, matters unfurl in new and unpredictable directions. Mark realizes his wife is being held captive by Lumon. She is working under an alias, seemingly without recollection of her identity. He needs to help his outie save her, but his feelings for Helly complicate the potential happily ever after. Helly realizes she is her own worst enemy, as her outie, Helena Eagan, treats innies like subhuman things. Dylan’s perception of everything changes once he sees his outie has a loving wife and three children, and Irving is heartbroken, having learned that Burt has a partner on the outside.

At the beginning of Severance Season 2, Mark wakes up alone on the severed floor, only to discover his whole team is gone, replaced with new workers. Disoriented and scared, he has no idea what has been going on since the MDR bunch had their consciousness briefly glance into the life of their outies. The atmosphere of emptiness and dread persists.

None of that, however, concerns Mark’s now boss, Mr. Milchick (Tramell Tillman), the man with the most disturbing smile. He promptly informs Mark that five months have passed since their “breakout”, labeled “Macrodata Uprising” by Lumon, who are now allegedly celebrating Mark’s team as faces of the “severance reform” and promising “better work conditions” for the innies. Assurances are made, and bizarre videos (with a voiceover by Keanu Reeves) are shown to placate workers, hailing a new age of improved work (i.e., living) experience for the severed folk confined to Lumon’s offices.

Of course, Mark is having none of this. Lumon’s overseers, among them Milchick, have been known to lie about every aspect of actuality, manipulating the existence of innies to their strange ends. The disconcerting aberrations continue as Milchick introduces Ms. Huang (Sarah Bock), a child, as his new deputy. As ever in Severance, nothing is what it seems, and reality is dubiously morbid.

Before he can do anything else, innie Mark endeavors to meet his team again, whose outies, Milchick claims, have asked not to return to work (unlike himself). On the other side of the power dynamic, Lumon’s drones will center their efforts around getting Mark to complete an extra secretive project called “Cold Harbor”, which we are told has to do with Gemma and might – wait for it – “change the world”.

What follows mustn’t be spoiled. In very broad strokes, we can say that innie Mark will surely meet his severed team again and that everyone’s quest for the truth will become complex in fresh ways through a deeper and often troubling connection between the innies and their outies. By the end of Severence Season 2, the compounding conflicts between Lumon and their employees (i.e., guinea pigs) will soar to the point of no return. The most impressive part of the story becomes the pivot toward a “private” notion of identity, the shift from office dynamics to each protagonist’s idea of self and what it can be once severed and split into different beings with differing ambitions.

Creativity and Problem-Solving

The developments of Season 2 show far more than the debut season, with the plot now centering on each of Severance’s main characters except Milchick. Mark, Irving, Dylan, Helly, Cobel, and their family members are all pulled to the forefront of the story, carefully intertwining and building to a series of climaxes in which the innies and outies clash in myriad ways. The mesh of intrigue is masterfully built by Erickson, a trained television writer, who mostly hits the tone and tempo right despite this project being his first showrunner.

Since we have exhausted the basic ideas behind the innies’ sad lives at Lumon Industries in Season 1, seeing that the showrunners still have no intention of (concretely) explaining the big mysteries of their foreboding workplace, it only made sense for Severance to make the outies the real focus of the fresh batch of episodes. As we learn more about each character’s “real” identity, every major notion of selfhood, including ideas of family, career, and relationships, will be questioned.

Excluding Milchick’s many woes in the throes of Lumon’s corporate chicanery, Season 2’s most affecting moments come from our acquaintance with the stories of the MDR team’s outie lives and how they choose to interact with their innies, who are now – shockingly to them – fighting for agency and voices of their own. Key players, including Cobel, get portions or entire episodes toward the end of the season, answering key questions about “what happened” to land them at Lumon and (of course) raising bizarre new ones.

This familiarization process is made spectacular by some excellent scene-setting, directing, and acting. With Severance bidding goodbye to its “funnier” aspects, such as parodying the tedium of office dwelling, off-kilter mystery paved the way for straight drama and horror. At times, Severance morphs into a surrealist/thriller. The show is too contained and self-referentially cryptic to be considered satire proper, but now even Milchick’s flamboyant burlesque is (mainly) set aside in favor of pervasive trepidation.

Scott, a dominantly comedic actor, steps up his game as the reluctant hero of the series, delivering a fascinatingly nuanced portrayal of the two Marks (inner and outie), whom, he helps us realize, are two very different beings with differing desired outcomes for themselves. In one of Severence‘s best scenes, he juggles his two “selves” simultaneously, passionately contrasting their subtle but diverse mannerisms and reactions. This won’t be the only time we evaluate an innie and outie (or the two Marks) against one another, and the intensity of innie Mark’s fear and defiance, coupled with outie Mark’s rage and anxiety is an emotional game-changer.

Suddenly, Lumon Industrie’s infinite lore will become trivial compared with complex existential ponderings; new depths of sympathy for the desperate innies, who become acutely aware they are not (just) at the mercy of their bosses, but their “real” selves, will overshadow everything else. While outie Mark embarks on a quest to “reintegrate” his two selves while attempting to save Gemma through innie Mark, we are left scratching our heads, wondering how these different personas could coexist in the same body. The realization that the innies are not only controlled by Lumon but also by their outies, who call the shots (mostly) on their innies’ employment (i.e., living) status, doesn’t lighten the mood, either.

The rest of the cast contributes just as much to Severance’s new emotional gravitas. Lower, in particular, shines as Helly R and Helena Eagan, two antithetical humans sharing a body. Helly, the beating heart of the MDR team, is fierce and defiant but disarmingly warm, curious, and brimming with life (and her tender feelings for Mark S.). Helena is a devil incarnate, a rigid, merciless heir to the Eagan empire who refuses to acknowledge innies as human beings.

Through numerous scenes with her abusive father Jame (Michael Sibbery), and aggressive Lumon enforcer, Mr. Drummond (Ólafur Darri Ólafsson), despite some “humanizing” moments of self-doubt, Helena is shown to be despicably icy. Little is learned about her motivation to sever. As she manically navigates crisis PR after Helly’s brief breakout, including a sterling standoff with the scorned Cobel, it becomes clear Helena has no intention of letting Helly survive for long. Lower remains impressive throughout this tense duality, switching between affable and repulsive with a simple smirk.

Turturro and Perry keep up the stellar balance, with Irving B. and Dylan G. both facing difficult realizations about their outies’ families and affiliations. Irving gets tangled up with Burt and his husband (an inscrutable John Noble). Dylan meets his (outie’s) wife, Gretchen (a fantastic Merritt Weaver), through Milchick’s manipulative attempt at pacifying and turning him against his team. Burt’s husband stays coyly in the background while Burt advises outie Irving on his next move. Gretchen, wonderfully fleshed out by Emmy-winning Weaver in a recurring role, has plenty to say about the detrimental effects of severance on families.

An understanding of outie Dylan’s motivations makes room for new scenarios in which an individual might choose to sever and have a large part of their life disappear with their innies. As mentioned, zooming in on the emotional aspects of being severed and the existential conundra the procedure creates is a hit, opening new interpretative horizons and marking a definitive shift toward psychological horror. The stories of friendship and loyalty that develop with the innies’ sense of the (impending) loss of what little life they cling to surpass the philosophical depth and aesthetic acuity to cement Severance’s place as one of the best television programs of our time.

It’s unfair to single out anyone amid a cast this strong and in harmony with their wildly demanding characters, but if there is a performance to shake you to the core in every scene, Tramell Tillman’s inscrutable Milchick is spellbinding. Hinging on prolonged silences and grueling closeups to supplant dialogue, Milchick’s expanded role as Lumons busybody is as fascinating as it is sinister.

Unsevered and promoted but stuck in his own version of hell called middle management, Milchick is continuously forced to navigate and endure the many indignities of (corporate) work. Enforcing Lumon’s policies brings him no pleasure, and neither does implementing every soul-crushing whim of theirs. What’s more, in Season 2 we experience Milchick as a resigned, apprehensive, or outraged employee himself, tangled up in far more mundane atrocities of being a corporate pawn than the innies’ outright science fiction scenario.

Tillman, of course, takes every advantage to disturb and impress as Milchick. Be it suppressed irritation at innies’ stubborn disobedience or muted revolt at a patronizing gift from the speaker-represented Lumon board, Milchick is the closest Severance has to an “ordinary”, if malicious and self-serving, person. Tillman is a perfect conduit for the negative feelings of a man disrespected by everyone around him. An undeniably powerful presence, he is at the center of Severance’s realistically represented components of work in neoliberal capitalism, particularly the setup in which what is verbally enforced directly contradicts material reality or the feelings of those who express the well-rehearsed words.

Indeed, every scene Tillman is in is a gem, especially another over-the-top, jaw-dropping finalé you will enjoy most if you know nothing about it. Praise is due for Sydney Cole Alexander, who embodies Lumon’s spokesperson Nathalie with friendly terror seldom seen… unless you’ve had to deal with your company’s Human Resources department.

Then there’s the singularly disconcerting aesthetic approach. Jeremy Hindle’s breathtaking production design of minimalist, vaguely retro-futuristic interiors in hues of green and blue, populated by little more than bodies and tools of labor and subsistence, adequately encapsulates the eerie silences of the perpetually frozen town of Kier. Elegantly drawing on the likes of David Hopper and his namesake Fincher, Hindle, Stiller, and the directing team, they visualize the uncanny to the nines through a profound understanding of the ways liminal spaces instill fear by omission, not accrual or succession (of things, bodies, spaces or time, including seasons).

The primary features of their aesthetic are emptiness and stasis, both incompatible with life and instantly frightening. In another aesthetic trick of the uncanny, all we see around the ever-so-slightly dystopian town of Kier is bare, as in makeshift houses posing as homes and barren expanses in between. Nature is covered in snow and shown mostly at night. Save for tokens of the cult of Eaganism, there is practically no sign of livelihood or history permeating the infinite darkness and desolation of the vast landscapes of which the people, including the outies, make little use.

Therefore, the setup of Severance remains firmly anti-Goethian, i.e., anti-life itself, where historiographies of communities and their customs disappear, replaced with artificial simulations of living that surpass even the nastiest of dystopian visions. Mark Scout’s and his sister Devon’s (Jen Tullock) houses, cafes and eateries, even the interiors of companies other than Lumon (no spoilers), all glare at the bodies populating them like basic renderings of a freshman modeler, devoid of any meaningful detail. Curiously, flashes of characters’ lives before severance are mostly set in spring, in deliberate stark contrast to the “severed” actuality of the present.

Beneath the many hopeful stories of love and life, paradoxically primarily coming from the wretched innies and not the “free-willed” outies, we are reminded that a world in which severance exists is, in its entirety, hell. It is a boldly political, self-contained statement: not having a structured, cohesive identity and a firm sense of self means not having any identity at all. In such a world, it is your masters alone (in this case, Lumon Industries or, more accurately, the Eagan dynasty) who decide on what history and meaning are. It is a bleak reality of extreme power imbalance run by depraved individuals and necessarily defined by emptiness or absence.

If this sounds familiar, rest assured it very much is; such is the uncanny brilliance of Severance. Defined aptly and in turn as the extended metaphor for enslavement, theft, surveillance, and control, the show has enough tricks up its sleeve to evade simple categorization. In so doing, Severence never loses sight of its true mission: to show us where we’re heading with our current postmodern and neoliberal developments.

Collaboration and Critical Thinking

Sure enough, Severance wouldn’t be what it is without mystery on top of outlandish mystery to keep the chronically online folks up at night guessing what even the slightest detail might mean. Mere weeks after the premiere, from the depths of Reddit and X to the most mainstream media you skim over while eating your morning cereal, theories about (potential spoilers follow!) Chladni plates, pineapples, and timelines overwhelm with specificity and analysis of details most casual fans don’t notice. In this respect, Severance Season 2 doubles down on the questions from the first season and enhances the confusion until the end.

This aspect of the show, a primary appeal to many, cannot be discussed without spoiling the entire season, but some general commentary is still due. The creative team remains as innovative and zealous as ever, so those hunting down every minute detail, from the types of fruits favored by Lumon’s staff to wristwatches, have heaps to look forward to. Nevertheless, every single answer comes with more questions and expanded narrative twists, in some cases widening the chasm between the viewers’ scope of understanding and the internal logic of the show’s reality.

Severance still wears its inspirations proudly on its sleeve, most notably the 2013 liminal space office nightmare video game The Stanley Parable (for more solid influences, read PopMatters‘ “Is There Life Beyond the Wall of Your Cubicle?” by John L. Murphy), but also another hit game, 2019’s Control. The latter is even more noticeable as inspiration in this new season, where corridors and spaces within Lumon start to shift the way they do in Control’s Oldest House, another colossal, quasi-brutalist edifice containing the totality of its employees’ lives. As in Control, uncovering secrets of Lumon’s building itself by overcoming, among other things, the horrors of bureaucracy and confounding rituals of the staff becomes central to uncovering Severance‘s mysteries.

To Erickson’s credit, he deftly deepened Severence‘s thematic potency by filling in the characters’ backstories and bridging the gaps between the innies and the outies, raising existential concerns that translate well to our lives. His ability to juggle piles of clues and Easter eggs, including a sly nod to Severance’s forebearer, LOST, by having Helly’s, Irving’s, and Dylan’s locker numbers correspond to Hurley’s lottery-winning digits, amazes while appearing effortless and unobtrusive to the main narrative. Nevertheless, how Severence‘s dozens (literally) of ever-expanding puzzles will be received by viewers remains to be seen.

Constructive Feedback

Meticulous and far-reaching as Severance is, some elephants (goats?) in the boardroom need to be addressed.

For one, the never-ending spirals of intrigue, while well-executed, might not be as warmly received by those who don’t get to binge the entire season in a matter of days. Some plots and cliffhangers take weeks to resolve, with many resolutions only deepening the confusion, evidently delaying the “real” answers. Seeing the showrunners plant clues and Easter eggs in fictional newspaper headlines and flashes on computer screens, though exciting for the die-hards, is likely to alienate a part of the viewership, even more so now that the primary investment lies with reconciling the innies and outies and seeing them reclaim their lives. Many auxiliary cliffhangers are long-forgotten before we return to them, and even then, with only partial resolutions, it becomes nearly impossible to put together a comprehensive picture of Severance’s universe.

Speaking of the show’s world, which is similar to our own, the internal logic fails to hold up in some key aspects. Too often we have to withstand situations in which intelligent, eloquent personalities act out of character and – despite being as confounded as we are – do some (big) things without question. Key scenes throughout Season 2 are most notably marked by a peculiar absence of dialogue and common sense, all for the sake of avoiding answers and resolutions, some of which are sorely needed after three years between the seasons. In this case, I put my speculative fan money on the reticent Burt knowing a lot more than he leads on, or maybe I just missed an entire batch of clues. Only time and diligent Redditors will tell.

There are logical problems with Lumon Industries’ position and operations, too. Unlike most works about exposing the big bad, in the world of Severance, Lumon is presented as an exploitative and dangerous organization people despise straight away. They might not be aware of its criminal activity, but the majority nevertheless don’t want to be associated with the company’s abusive panopticism (some real-life corporates come to mind).

Helena’s/Helly’s plot notwithstanding, it is becoming increasingly difficult to understand why any of the main characters, despite their emotional troubles, would agree to be severed. Severance goes out of its way to explain this in Mark’s and Dylan’s case, but the setup is unconvincing. Lumon’s cronies might be a part of an ambitious hellish cult, but the public predominantly wants nothing to do with them.

It is difficult to envision anyone, let alone an emancipated intellectual like Mark Scout, literally handing their body over to these monsters, grief or no grief. No corporation with the ability to control bodies and memories would shy away from committing atrocities with them, and Lumon Industries, with their insane mythology, appears to be notorious as is. Knowing that severed jobs are, by definition, “unqualified” (any educational profile can do them), plenty of suspension of disbelief is needed to explain why these smart people would willingly submit themselves to something so shady as allowing themselves to be severed.

As Severance progresses, we witness all but incredible levels of innie conspiring across Lumon Industries’ severed floor, as if the most comprehensively control-oriented company in the world is oblivious. We are led to believe there are no cameras, bugs, or other surveillance methods, as the innies appear free to conspire through dialogue, gestures, planting clues, and even outright ventures into “forbidden” corridors. Surely, all of this might prove to have been done with Lumon’s knowledge all along, but so far it doesn’t seem like it.

Glossing over common sense to move the plot forward isn’t uncommon in mystery dramas or thrillers, in Severance, this overlook seems too extreme at times. It is difficult to imagine that a company holding people captive on otherwise closely monitored premises has no idea when the captives are messing about, even more so when they are known for insurgency.

Adding layers upon layers of the unknown with a deliberate side of confusion doesn’t help, either; by the time Season 2 ends, you are left with the impression that you know even less than you did at its beginning. Deliberate as this is, it can also feel like a cheat to prolong a series that is not set up to last more than a couple of seasons (few characters and essentially one big central puzzle with several smaller ones orbiting).

A lot happens in Season 2 – some of it monumental – but the responses to an often partial reveal after hours of breadcrumb clues are underwhelming. Some of the new information we are served as a hot new plot or a grand realization is rather commonsensical or seems misaligned with what we perceive as the show’s reality. Perhaps the best example of this was finding out about “the purpose” of herds of goats being bred on simulated grass plains within “Mammalians Nurturable”, another bizarre underground department of Lumon’s. After hours of glances at nursing baby goats across the severed floor, we get a comprehensive explanation for why the goats are bred there, except it is such a simple conceit there is no reason for keeping the animals indoors.

It’s unbecoming and naïve to presume that works of art need to be realistic – they are about evoking emotions and affective responses. However, in Severance, too much makes too little sense too often. When this sense of bewilderment is extended to the explanations, it is no longer unreasonable to wonder if some of the components of suspense are mere gimmicks.

Without getting into spoilery detail, on top of the sheer amount and insistence of puzzles, another considerable issue with Severance is the inexplicable narrative fixation on Kier Eagan. From Kier Easter eggs in Season 2’s opening credits, which have warranted standalone articles in various media, to relentless reminding that everything Lumon Industries does is directly inspired by him, his ghost, or maybe the idea of his resurrection or cloning (pure wild speculation), not an episode can go by without several or more cryptic and odd references to the great Kier Egan. Besides our investment in Severance shifting away from the eerie enigma toward the emotional resolution of the protagonists’ lives, one of the rare things the otherwise capable showmakers don’t seem to understand is that it doesn’t matter who Kier Egan “really” was and what Lumon “really” wants to do with him or his memory.

In a world where we hear daily about billionaires taking their own sons’ blood in pursuit of eternal life, forming para corporate teams of teenagers named after a meme to dismantle a government (with their president’s blessing), or having whistleblowers die under strange circumstances, no sci-fi imagery of a powerful buffoon wanting more power feels remotely surprising or even relevant. Necessary as it perhaps is for explaining some aspects of Severance, the story of Kier Eagan doesn’t warrant nearly so much scrutiny. He was just another powerful mofo who wanted to be all-powerful and control everything, like most other rich mofos.

Whether the Big Truth is that he wanted to clone or resurrect himself, or have Lumon Industries control the planet’s workforce by installing chips into people’s brains (cue real life), or maybe colonize other planets with the severed folk (real life takes the cake here, too), it doesn’t matter. It’s all the same damned ambition by all these callous, self-serving enemies of the people. The point is that every conceivable reveal about Kier Egan will have the same, diminished affective impact, as all these characters, fictional or otherwise, come from the same place of blind ambition, they all want(ed) a cult following, to be worshipped and obeyed. Maybe Severance will prove me wrong, but as of now, having Kier Egan at the center of it all comes across as tired and unnecessary.

Finally, while acknowledging Severance‘s overall thematic brilliance and complexity, I lament that it mostly stopped being a show about its former primary building block: labor. This is not a negative criticism, as the showrunners have every right to decide on the flow of their work, but workplace parody and corporate satire drew many of us to the show. While we started off making morbid fun of the idea of corporate work as a neverending hell of meaningless toil, ennui, and patronizing gestures by our scheming managers, now only Milchick’s story remains within this remit.

Relevant as other developments may be, the astute examination of workplace ethics has always been one of Severance’s most accomplished and politically pertinent aspects. It’s sad to leave this most scathing indictment of not just one company but the entire system shaping our daily experiences behind.

Developmental Suggestions for Goal Achievement

All things considered, Severance remains the most thoroughly original drama to emerge in a long while – at least since The Leftovers or maybe Evil. It is a maze of intrigue and aesthetic experimentation but with an enormous heart and emotional maturity to ground it.

Having come at least halfway by now, the profundity with which it dishes out hard emotional truths and the detail with which it examines the so-called human condition through the prism of hard science fiction and mystery are shaping Severance as a show for the ages. It is to be expected that the sci-fi genre, if not television itself, will be measured against it for years to come. With the third season writers’ room underway, we hope we won’t have to wait another three years to hear more about the strange story of Mark, Helly, Dylan, and Irving.