Erich Von Stroheim’s films fetishised a scandalous poke to the public’s eye, whereas Cecile B. DeMille’s films obsessed over middle-class verities.

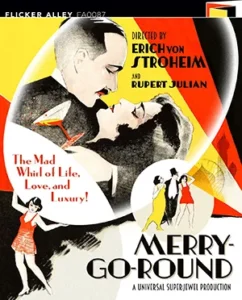

Merry-Go-Round Erich Von Stroheim Flicker Alley 18 March 2025

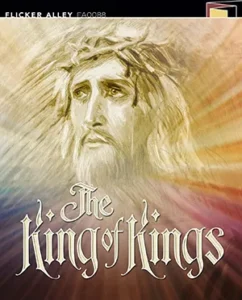

Merry-Go-Round Erich Von Stroheim Flicker Alley 18 March 2025  The King of Kings Cecil B. DeMille Flicker Alley 12 May 2025

The King of Kings Cecil B. DeMille Flicker Alley 12 May 2025

Flicker Alley, one of the most important promoters of silent film heritage, has issued new Blu-ray restorations of two major epics of Hollywood’s 1920s. Both projects could be called miraculous.

Rupert Julian’s Universal Super-Jewel, Merry-Go-Round (1923), is actually Erich Von Stroheim‘s Merry-Go-Round, or it was until Universal got fed up and fired Stroheim. This behind-the-scenes story is as fascinating as what’s on screen.

A bonus on the Blu-ray is a crucial earlier film in Stroheim’s filmography: Old Heidelberg (1915), directed by John Emerson and produced by D.W. Griffith. This film was important for launching Stroheim’s tone and stardom upon an unsuspecting world.

As for Cecil B. DeMille‘s The King of Kings (1927), this celebrated filmmaker’s second massive Biblical epic is a stunner. The two-disc release includes both the restored roadshow version, which runs two hours and forty minutes and includes two sequences in early two-color Technicolor, and the shorter 1928 reissue that played regular theatres with a music track attached.

Erich Von Stroheim the Old Scoundrel

Ever since young Erich Von Stroheim immigrated to America from Austria and added the “Von” to his name, he’d been reinventing himself as a fallen aristocrat instead of the son of a Jewish merchant. His penchant for class-conscious storytelling and similar fabrications found a perfect outlet in Hollywood, which didn’t always (or ever) appreciate him.

After working for a while with D.W. Griffith, Von Stroheim bluffed his way into a supporting role and assistant director on Old Heidelberg (1915). As film historian Richard Koszarski tells the story on his highly informed commentary track, director John Emerson asked the company if anyone had knowledge of Heidelberg University, and Von, as he was called for short, stood up and declared himself a graduate. His career was underway with himself as his greatest creation.

That anecdote explains something about Old Heidelberg. This very popular German play by Wilhelm Meyer-Förster, based on his 1898 novel, tells the bittersweet romance of a love between a prince and an innkeeper’s daughter. Because of the class difference, their love can’t be sustained after he ascends to the throne.

In its original form and many later incarnations, Meyer-Förster’s story is fluffy Viennese pastry in a fairy-tale setting. It’s got nothing to do with war, but Emerson’s film injects a war into the plot that kills and maims the country’s young men, leading to much bitterness in the people. When a new war looms because of the prince’s hard-headed papa, the prince disagrees with his old man.

Meanwhile, the outraged populace makes pacifist speeches and swarms to protest, almost leading to riot and bloodshed, before the father is conveniently struck down by the hand of God. These elements resonated with the current European conflict, in which the United States wasn’t yet involved.

As Koszarski explains, these added twists, with their sour comments on the arrogance of class and power, reek of the type of material Erich Von Stroheim would put in his films. His own supporting role as the stiff-backed, crewcut, unlikable valet already forecasts his persona as “the man you love to hate”. That’s how he got advertised in the coming wave of anti-German war propaganda movies in which he played evil Huns, and he milked that reputation when making his own films and casting himself as scoundrels.

How much of the interpolated material in Old Heidelberg, and the details about uniformed students who specialize in singing and drinking beer from steins, comes from Von Stroheim’s contributions? Or was he simply influenced by this material? We’ll never be sure, but the link is clear.

On and off Erich Von Stroheim’s Merry-Go-Round

From the start of Eric Von Stroheim’s career as an auteur, his films courted controversy and publicity. PopMatters has already discussed the splashy fiasco that was Foolish Wives (1922), the film that got taken out of his hands by studio watchdog Irving Thalberg. His next project was Merry-Go-Round, upon which Thalberg kept such a tight watch that Stroheim finally got fired and replaced by Rupert Julian, who had also made a reputation playing evil Huns in war propaganda.

Von Stroheim’s name was nowhere on the release print of Merry-Go-Round, although it was uniformly reviewed in the light of what everyone knew about Von Stroheim’s firing. Critics speculated over the extent to which it had been ruined or was still visibly Von Stroheim’s work.

Julian defended himself by explaining he directed virtually everything in Merry-Go-Round after the opening reel, and he revised Von Stroheim’s scenario for a happier ending in which not so many characters get maimed or kill themselves. Still, the conception and look of this non-Von Stroheim film has his fingerprints all over it. As Koszarski says, “Julian was an opportunist but he was no fool.”

It was easy to fire Erich Von Stroheim because he was forbidden to star as Count Franz Maximilian Von Hohenegg, whose name sounds like a joke. The Count is played by Norman Kerry, one of the silent era’s dashing leads. In what’s clearly a Von Stroheim-directed scene, we see the Count being roused from sleep by his valet. The sleepy Count imagines the valet’s hand on his shoulder must be his sweetheart’s and caresses it while the valet smiles.

Then, in his long nightgown, the Count playfully leaps over the crouching valet’s back before shedding his gown (closeup on his feet) and stepping into a deep tub. Audiences knew they were in Von Stroheim country with all this winking fetishism and eroticism.

The story at large, which manages to be simple and overstuffed, involves people who work at the Prater, Vienna’s outdoor amusement park, complete with a Ferris wheel. Mary Philbin, who would team up again with Kerry in Julian’s monumental The Phantom of the Opera (1925), plays the winsome organ-grinder, Agnes, who functions as our innocent heroine.

Agnes takes abuse from bullying boss Huber (George Siegmann), looks out for her cowering puppeteer father (Cesare Gravina) and dying mother (Edith Yorke), and is loved by a handsome young hunchback Bartholomew (George Hackathorne), who’s in charge of a large real orangutan. We’re all Fate’s puppets, and we’re all courting the orangutan. It will take years of melodrama and war before Agnes and the unworthy Count, who picks up a wife (Dorothy Wallace), can have a supposedly happy ending.

The audience can hardly care much about what happens to the Count or even Agnes. It must have been Erich Von Stroheim’s idea to intersperse the plot developments with a symbolic motif of a ripped and shirtless laughing devil or perhaps a faun, in either case a symbol of nature and libido that won’t be controlled by civilization, who stands in the center of an endlessly twirling circle of little models on an existential wheel.

The devil drives home the point that the characters of Merry-Go-Round are mere playthings of either mechanical forces or whimsical and malevolent Fate, or both. They’re no more in control of their destinies than ordinary people are in control of whether their countries go to war, and that’s a harking back to Old Heidelberg.

The sour, dispassionate hand of Fate, expressed by divisions among classes, nations, and sexes, is a recurring foundation of Von Stroheim’s vision. His perfectionism and willingness to spend the studio’s money on films that were extravagantly “too long” are the other crucial parts of his legend. Sadly, he was a century ahead of the eight—and ten-hour Netflix epics on which people happily binge today.

Flicker Alley’s Blu-ray comes as close as anyone probably can to restoring the cause célèbre that is Merry-Go-Round. As restorationist Serge Bromberg explains in the notes, this new edition begins with the three 16mm prints used in the 2003 restoration and combines them with a truncated 35mm print in an Austrian archive. The footage from Austria is as sharp as we’d like, and includes tints and colors in the early fireworks and fairground sequence, while the US prints tend to be soft. Even with imperfections, the reconstruction of this notorious 1923 production is something of a miracle.

Sinful Flesh in Cecil B. DeMille’s The King of Kings

Cecil B. DeMille also made expensive and extravagant epics full of sinful flesh, and he understood that by tempering them with moralism and religious piety, he could sell them in Peoria. After a stream of sophisticated sex comedies and melodramas at the start of the Roaring 20s, he made the effects-laden The Ten Commandments (1923), one of its era’s most thunderous box-office hits (and a film with mild nudity). Having mined the Old Testament for that epic, The King of Kings became DeMille’s second trip to the Bible, this time for the New Testament chronicles of a nice Jewish boy.

It’s brilliantly done. Cecil B. DeMille sometimes receives critical smirks for the Barnum-like showmanship with which he plays to the groundlings and for his belief in straight-faced kitsch, but he does all this seemingly with deep conviction, not cynicism. It’s a form of compartmentalizing, perhaps, but he feels obligated to give the public what it wants to lap up, and he feels right and proper about it.

The King of Kings needs no apology or contextualizing. It’s effective and emotional from the get-go, as the stunning clarity of this restoration reveals in all its splendor. The film moved audiences in 1927 and retains its power to do so.

Consider the first act. Against the early Technicolor of a sunrise illustration, we’re told: “This is a story of Jesus of Nazareth … He, Himself, commanded that His message be carried to the uttermost parts of the earth. May this portrayal play a reverent part in the spirit of that great command.” DeMille and his longtime writer and collaborator, Jeanie MacPherson, imply that they’ve received their commission directly from the Almighty.

Next, we’re told, “In Judea, groaning under the iron heel of Rome, the beautiful courtesan, Mary of Magdala, laughed alike at God and Man.” We see the glorious Technicolor spectacle of this decadent pageantry, with Mary (Jacqueline Logan) lounging half-naked in a virtually painted-on dress. Her hair is decorated with snakelike S-bangs (1920s stylish), and she sports an enormous red bauble on her right index finger.

Servants or slaveboys strut like clones in blond helmet do’s, pulling a sheer curtain in front of musicians while primped and leering male guests eat and drink. These include Sojin, a Japanese star, as a Persian. Exotic dancer Sally Rand is in there somewhere. The human and animal menagerie includes a turbaned capuchin monkey, a roaring leopard leashed by his female trainer, and flapping swans. It’s the high life, perhaps not far removed from some Hollywood parties, or so we may hope.

In a bit of creative license, we’re told that Mary’s boy toy is none other than Judas Iscariot (Joseph Schildkraut), portrayed as an effete political schemer. She flies into a jealous rage when she hears he’s hanging out with a carpenter. She tells a charioteer (Noble Johnson, who founded the first African-American film studio), “Harness my zebras, gift of the Nubian King! This Carpenter shall learn that he cannot hold a man from Mary Magdalene!”

When told the carpenter has cured the blind, she responds, “I have blinded more men than He hath ever healed!” When told he’s raised the dead, she points at herself and says something not revealed, but the startled response of her listeners gives a darn good idea of what sauce she’s dishing.

All this, of course, is campy kitsch, and therefore a vital part of Hollywood’s artillery. What matters is that it’s done delightfully and impeccably, complete with those fabulous harnessed zebras, and we’re set up for the contrast of what happens next in the humble carpentry shop.

Here, The King of Kings reverts to black and white, a sign of humility and clarity, as we find crowds of people clamoring to see Jesus. Several character interactions deftly sketch social and political details, and we focus on a little blind girl (Muriel McCormac) brought forth by Mother Mary (Dorothy Cumming), who’s been working a loom. In close-up, the girl begins to exclaim that she can see the lighting effects rising around her.

Then, in a touch of true creative brilliance that separates the artists from the hacks, H.B. Warner as the bearded Jesus is finally brought into focus before the viewer and simultaneously to the girl as the first thing she ever sees. He looks into the camera with forbearance and a kind of sad love as we all receive the grace of his regard.

As historian Marc Wanamaker reports in the commentary, audiences were widely reported as moved to tears by the simple magic and emotion of the scene, and that’s not hard to believe. Nor is that all. At this moment, haughty Magdalene with her zebras blows into the scene to confront her errant boyfriend and get a load of this upstart carpenter.

Just one look, that’s all it took, and this is a mark of how consummately Logan plays the scene under Cecil B. DeMille’s direction. “Be thou clean,” says Jesus, and her imperious mien drops haltingly into confusion. Multiple images of herself as the various deadly sins now surround her via superimposition, beseeching her not to forsake them. When the last of them has vanished, Mary looks down at her dress (or lack of it), modestly veils her cape about herself, and bends to kiss the hem of His garment.

This is exactly the kind of thing that silent films pull off perfectly, dispensing with dialogue in favor of simple visual effects and minutely executed gestures and expressions. Dialogue and sound may tend to reduce the emotional impact by rendering it all too literal, too much of this world, whereas silent artistry transcends mundane considerations and casts viewers into the uncanny spell, bypassing our intellect to electrify the heart to the accompaniment of the musical score. It just works. No amount of description can convey the viewer’s experience. Those who have eyes to see, let them see.

Doppelgangers in Artistry

We could proceed through all scenes of The King of Kings in their perfection of detail, pace, and expression over two hours and forty minutes, but it’s unnecessary. Cecil B. DeMille and his massive studio crew and cast were at the top of their form. The Resurrection is also in Technicolor, and the torches at Gethsemane are hand-colored. The cast includes Rudolph Schildkraut (Joseph’s dad) as Caiaphas, Ernest Torrence as an outsized Peter, Sam De Grasse as a scheming Pharisee, Victor Varconi as Pontius Pilate, Majel Coleman as Pilate’s wife, George Siegmann (the baddie in Merry-Go-Round) as Barabbas, and many others.

We’re describing the full roadshow version, the first film ever to play at Grauman’s Chinese Theatre. A second disc contains a shorter version that omits much and adds a music-and-effects track, with an alternate secondary soundtrack. We get 20 minutes of behind-the-scenes footage plus promo films (one of which is animated) and pieces on the hand-stenciled colors in one segment, the creation of dual negatives, and the early Technicolor process. Thanks to the miraculous discoveries of lost prints, the color segments have been digitally restored to a clarity not seen in almost a century. As Bromberg states, it’s truly a resurrection.

The discs’ discussions of their filmmakers bring out the similarities between Erich Von Stroheim and Cecil B. DeMille. Both were hard-headed autocrats with fetishistic streaks a yard wide. They both believed in research and authenticity. The difference is that DeMille was content to let studio artisans fabricate everything after researching the proper items and costumes. Von Stroheim wanted nothing less than the original articles to be imported.

DeMille was a political conservative who only became more so. He had his hand on the public pulse in a way that made him more consistently successful with the studios and the ticket-buyers than Erich Von Stroheim was. Erich Von Stroheim believed in giving the public a scandalous poke in the eye. DeMille believed in bread and circuses that reinforced middle-class verities. They are each other’s Hollywood doppelgangers who left us with seductive cinematic legacies of extravagant gestures and genuine artistry.