One Way Home doesn’t revolutionize childhood horror; it’s part of the evolution of a subgenre that continues to find new ways to explore familiar fears.

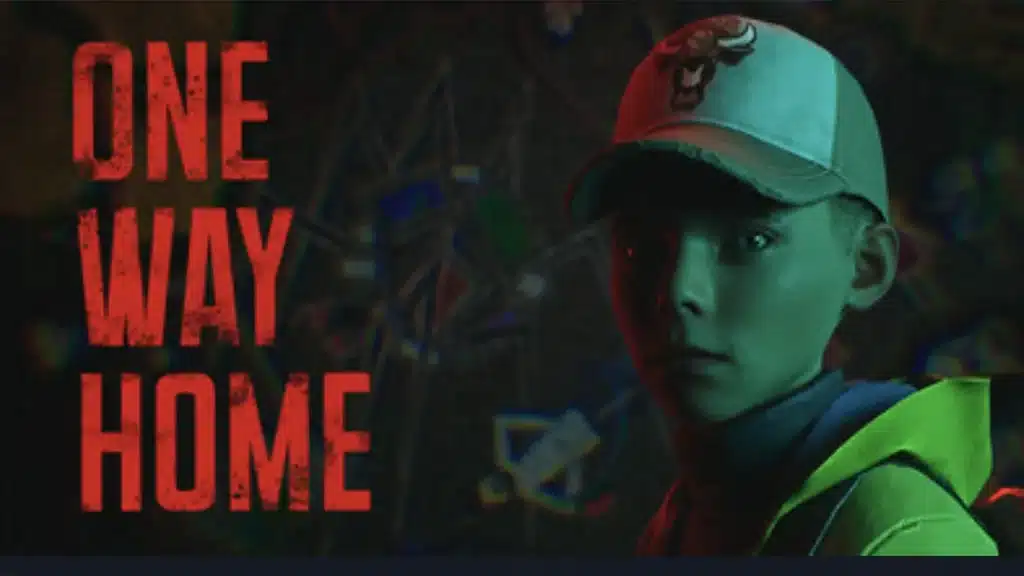

One Way Home CYBERHEAD 2026

One Way Home CYBERHEAD 2026

One Way Home intimately understands a primal fear. Jimmy Taylor, waking up after a bus crash to find his hometown transformed, taps directly into a specific subset of childhood horror: the purgatorial space where trauma suspends children between life and death, reality and nightmare. This liminal horror has deep roots across media, yet its evolution reveals fascinating cultural blind spots.

Literature established the template with works like C.S. Lewis’ The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe (1950), where children escape trauma through doorways into other worlds that reflect their psychological states. Cinema explores how near-death experiences could trap children in spaces that mirror their fears; M. Night Shyamalan‘s The Sixth Sense (1999) reveals how death creates a kind of stasis where the traumatized remain frozen in their moment of terror.

As explored in Nathanial Gage Pennington’s 2019 Radford University thesis, Stephen King’s American Vision from Childhood to Adulthood, King’s fiction corrupts childhood psychological spaces through trauma, fear, and repression shaped by distinctly American cultural anxieties. The town of Derry in King’s 2017 supernatural horror film IT represents the quintessential American nightmare: the small town as an ultimate safe space violated by ancient evil. This differs markedly from European childhood horror traditions, which typically center on forests (the German fairytale Hansel and Gretel) or institutional spaces rather than suburban corruption.

Katie Krentz and Patrick McHale’s animated folk horror miniseries Over the Garden Wall from 2014 perfected this American conception for contemporary audiences: two brothers lost in a mysterious forest after what’s strongly implied to be a near-fatal accident, navigating a purgatorial realm that’s equal parts whimsical and terrifying. The Unknown becomes a space where childhood fears and adult anxieties blend into something fantastical and devastatingly real, where being lost isn’t just physical but existential.

Interactive media has found unique ways to embody this liminal state. Limbo (2010) places its protagonist in a space between life and death, while Little Nightmares (2017) creates institutions that are corrupted versions of spaces meant to nurture children. Yet these games, influential as they are, represent only one strand of childhood horror’s psychological complexity.

One Way Home‘s Hometown Gothic Tradition

One Way Home draws directly from what critic Joyce Carol Oates identified as Stephen King’s “characteristic subject“, small-town American life, where familiar spaces become threatening. King’s Derry, explicitly modeled on his hometown of Bangor, Maine, established a template for American childhood horror that One Way Home directly inherits: the hometown as a psychological landscape, where trauma transforms the geography of safety into a map of terror.

This represents a distinctly American horror tradition. Where European folklore corrupts natural spaces (dark forests, ancient castles), American childhood horror violates the suburban ideal, the promise that small towns and familiar neighborhoods represent safety from the wider world’s dangers. Jimmy Taylor’s transformed hometown operates in this tradition, where police cruisers and streetlights become sources of threat rather than protection.

One Way Home‘s setup is deceptively simple: 12-year-old Jimmy wakes up after a bus crash to find his hometown transformed into something hollow and threatening. Shadows move where they shouldn’t, and the comforting landmarks of childhood are twisted into something sinister. It’s a premise that calls to mind Limbo and Inside (2016). However, One Way Home‘s approach to childhood terror distinctly differs from Playdead’s minimalist nightmares, at least based on the game’s opening act, available as a free demo on Steam.

The Psychological Mechanics of Corrupted Safety

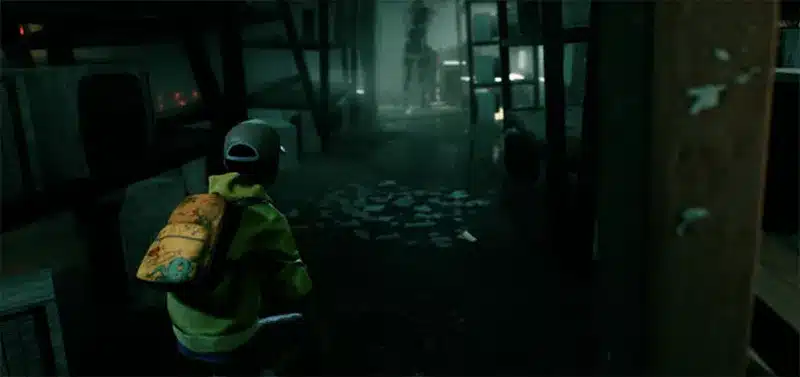

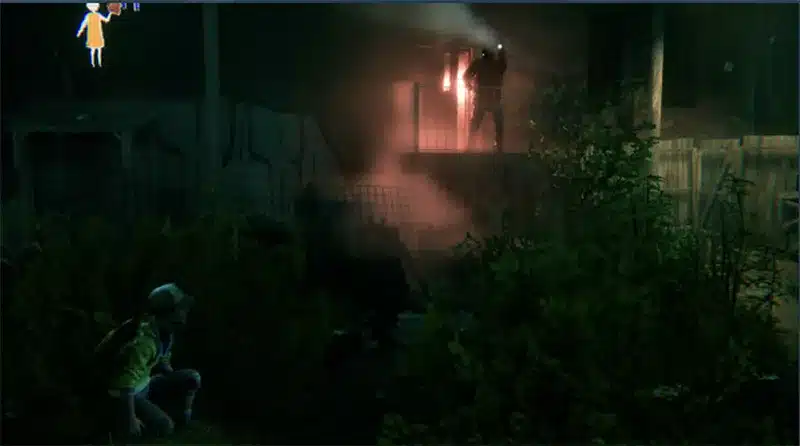

The game’s most sophisticated element lies in its mechanical representation of trauma’s effect on threat detection. One Way Home‘s light-and-shadow dynamics brilliantly invert childhood’s typical relationship with safety: darkness means protection, while well-lit areas represent imminent danger. This reversal isn’t just atmospheric; it mirrors documented psychological research on how trauma survivors develop hypervigilance, where the usual safety cues become unreliable.

Research shows that trauma can alter threat detection, creating a heightened state where survivors may experience enhanced sensitivity to stimuli and develop hypervigilance even in safe environments. Jimmy’s world literalizes this psychological reality: the bright streetlights that should signal safety become beacons for the shadow creatures stalking him. This isn’t merely clever game design; it’s an authentic representation of how childhood trauma can make familiar spaces feel alien and threatening.

One Way Home‘s stealth-based gameplay reinforces this dynamic. Jimmy can’t fight the distorted creatures stalking him; he can only hide, run, or use his environment cleverly. His survival tools are grounded in the resourcefulness of childhood: throwing objects to distract enemies, finding small spaces to hide, and turning his small size into an advantage rather than a limitation. There’s something poignant about watching this 12-year-old avatar navigate danger with the kind of quick thinking that kids develop when they can’t rely on adult protection.

The Interactive Evolution of Universal Fears

To understand what One Way Home accomplishes, we need to recognize how games have refined childhood horror’s approach to universal anxieties. Early horror games borrowed adult horror tropes, but the breakthrough came with recognizing that childhood fear operates differently; it’s about specific limitations and vulnerabilities that adults have forgotten.

Limbo captures the exhausting hypervigilance that every child knows: how you must constantly scan for threats when you realize the world isn’t inherently safe. Inside taps into childhood’s dangerous curiosity, that compulsion to investigate things we know we shouldn’t, driven by the need to understand a world that adults won’t fully explain. Little Nightmares brilliantly explores the universal childhood experience of navigating spaces designed to exclude us: kitchens with counters too high, doors with handles we can barely reach, authority figures whose true nature is hidden behind pleasant facades.

Where these games use child protagonists primarily as vessels for atmospheric dread, One Way Home attempts something more psychologically complex. Jimmy Taylor doesn’t just represent “generic childhood peril”; he embodies the specific anxiety of being 12, caught between the safety of childhood dependence and the terrifying realization that he might need to survive on his own.

This evolution is exemplified in how the game uses environmental storytelling. Throughout Jimmy’s journey, childlike drawings appear on walls and surfaces, some of which animate to reveal fragments of backstory. These aren’t formal mechanics; they’re environmental details that use the visual language of childhood to hint at Jimmy’s past or fears. When these crude drawings suddenly come to life with surprising emotional weight, CYBERHEAD makes the child’s perspective central to narrative and gameplay in ways beyond just having a young protagonist.

The Weight of Innocence

One Way Home‘s horror derives not from abstract existential dread but from recognizable childhood anxieties amplified to nightmare proportions. During the demo session, watching Jimmy narrowly escape shadow creatures by diving behind a dumpster seems less like a game mechanic and more like witnessing genuine fear. However, hints suggest these creatures aren’t entirely foreign to Jimmy; he mentions recognizing at least one of them, indicating these nightmares are manifestations of his own fears rather than external threats.

The choice-driven narrative addresses one of the genre’s long-standing limitations. Where most childhood horror platformers offer single, linear experiences of trauma, One Way Home demonstrates that different choices and paths lead to different kinds of growth and resolution. The game offers distinct character development paths – the Sage, the Innocent, or the Explorer – each promising to shape not just story outcomes but Jimmy’s fundamental approach to processing his experience. How these playstyles will differ in practice remains to be seen.

This approach to character development reflects a broader understanding that CYBERHEAD’s seven-person team brings to the genre. They’ve studied game developer Playdead’s work closely, borrowing their side-scrolling perspective, physics-based puzzles, and atmospheric storytelling techniques that define their games. However, where those protagonists remain enigmatic ciphers for player projection, Jimmy is a specific person with his own interior life.

One Way Home‘s environmental storytelling elements work because they appear connected to Jimmy’s psychological state, though their significance remains to be seen. However, the game’s dialogue occasionally becomes overly explanatory, spelling out emotional beats that would be more powerful left implicit. There’s a delicate balance in childhood horror between honoring the protagonist’s perspective and maintaining the mystery that makes horror effective.

Still, the branching narrative system and multiple endings confirm a more complex understanding of how childhood experiences can shape us in multiple directions. One Way Home demonstrates that childhood trauma isn’t a monolithic experience with a single resolution.

Growing Up Scared

One Way Home represents exactly what childhood horror needs: a game that understands the genre’s core strengths while thoughtfully expanding its emotional vocabulary. CYBERHEAD has built upon the atmospheric dread and environmental storytelling that made games like Limbo and Inside so influential, while adding layers of psychological complexity that are both mature and true to how various children might process similar events.

What’s most impressive is how the game maintains the genre’s essential atmosphere while engaging with the distinctly American tradition of hometown gothic horror. By placing Jimmy in a corrupted version of his familiar spaces, One Way Home connects to a lineage from King’s Derry through the supernatural horror series Stranger Things’ town of Hawkins. These stories help us understand how the violation of familiar geography also violates childhood safety.

The animated drawings that appear on walls and surfaces work in One Way Home because they seem connected to the broader childhood horror aesthetic, while Jimmy’s voiced reactions enhance rather than compete with the environmental storytelling. CYBERHEAD demonstrates a clear affection for childhood horror’s established tradition; their contributions emerge organically from that understanding.

One Way Home doesn’t revolutionize childhood horror, but it doesn’t need to. Instead, it represents the steady evolution of a subgenre that continues to find new ways to explore familiar fears. The game’s thoughtful approach to psychological authenticity and connection to the broader American Gothic tradition demonstrates that there’s still room for meaningful entries in this space for games that understand where the genre has been and where it might go next. Sometimes the most valuable contributions in video games aren’t the ones that break new ground, but the ones that cultivate it carefully.