For Crying Out Loud: How Louie Anderson’s televised therapy sessions created the saddest, funniest cartoon of the 1990s.

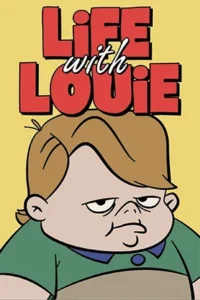

Life with Louie Louie Anderson Fox 1994-98

Life with Louie Louie Anderson Fox 1994-98

One of the most radical acts of therapy in the 1990s didn’t happen on a therapist’s couch, but in a cartoon, broadcast on Saturday mornings between commercials for L.A. Gear light-up sneakers and the technicolor sugar-blast of Cap’n Crunch cereal for kids. The show was Life with Louie, and its creator, the late comedian Louie Anderson, used it to stage a weekly séance with his past.

Anderson took the terrifying ghost that haunted his childhood, his violent, alcoholic father, and rewrote him. He didn’t erase the man’s flaws, but he softened the rage into complaint, filtered the abuse into absurdity, and in doing so, performed a gentle exorcism in the 8:30 a.m. time slot.

To watch Life with Louie, which aired on Fox from 1995 to 1998, was to enter a world of planned drabness, committed to the muted ochres and dull blues of a perpetual Wisconsin winter. In an era of animated hysteria, when its schedule-mates were mutants saving the world or the anarchy of Eek! The Cat, here was a show whose dramas revolved around acquiring a bicycle horn or joining the chess club.

Yet it was in this cultivated mundanity that Life with Louie revealed its strange and enduring power. It wasn’t just a children’s cartoon; it was a public reckoning with a private history.

Portrait of a Father as a Rambling War Machine

Life with Louie was the semi-autobiographical creation of Louis Anderson, who voiced both his eight-year-old self and the formidable figure at the centre of his universe: his father, Andy Anderson. Animated Louie is a nervous, sensitive child, a soft, doughy figure navigating Midwestern boyhood. The show’s true gravitational force, however, was Andy, a human weather system all other characters had to navigate.

A veteran of World War II, a fact he deployed with the strategic subtlety of an anvil, Andy was a vessel of near-constant complaint whose worldview was a fortress built of thrift, suspicion, and old-school American grit. Critically, his life lessons were cryptic, often nonsensical koans wrapped in the husk of his past traumas.

This is perfectly illustrated in an episode centered on chess. When young Louie discovers a talent for the game, Andy doesn’t foster it; he relentlessly warns him that chess players are mocked and scorned, a direct transfer of anxiety from father to son. Fearing this ridicule, Louie competes in a tournament while hiding his identity as “The Masked Chess Boy”.

The crucial act of grace the show affords Andy comes in the climax: it’s revealed that Andy himself was the original Masked Chess Boy, having invented the persona decades ago to hide his passion for the game from bullies. What seems like cruelty is reframed as a tragic attempt to shield his son from the same hurts he endured.

Nowhere was Andy’s true character more evident than in his relationship with the family car, a Rambler that was as much a metaphor for his soul as it was a vehicle. Perpetually on the verge of collapse, the car ran on little more than old-school stubbornness. For Andy, the Rambler was a testament to his own resilience.

In one episode, after the car finally breaks down, his wife Ora buys him a new one. A normal man might be grateful, yet Andy is deeply insulted. The new car is an admission of defeat. He tries to adapt but in the end he rejects the new car, choosing instead the (in his mind) noble, familiar struggle of keeping his broken-down chariot running; a hilarious and poignant portrait of a man clinging to a failing piece of machinery because, like him, it was a veteran of a bygone era.

A Son’s Radical Empathy

This portrayal of Andy as a formidable yet lovable patriarch becomes an act of reinvention when considering the reality. In his searingly honest memoir from 1991, Dear Dad: Letters from an Adult Child, Louie Anderson painted a far bleaker picture. The real Andy wasn’t a sitcom dad but a violent, unpredictable alcoholic whose outbursts were genuinely terrifying. The comedian’s childhood wasn’t gentle melancholy, but the nerve-shredding vigilance required to survive the whims of an addict. Anderson recalled becoming so sensitive that he could tell if his father had been drinking the moment he walked in the door from school.

The real Andy didn’t just complain; he carried a gun and would menace his children with a “Click-click!”. He would get drunk and beat up the neighbour, Mr. Wilson, yelling, “Come on out, you chicken-shit bastard!”. The cartoon catchphrase “For crying out loud!” was a heavily sanitized echo of a far more frightening reality, one where Anderson was woken up in the middle of the night by his father yelling, “Hey, lard ass, when ya going to lose some weight?”.

The source of this rage, for most of Louie Anderson’s life, remained an unsolvable riddle. Then, late in his father’s life, came the revelation. During a hospital visit, Anderson overheard his father, weakened by cancer, finally confess his history to a social worker. Louie’s monstrous father had been a wounded child himself.

His parents were alcoholics who, when he was just ten years old, took him and his sister to their church and put them up for adoption in front of the entire congregation. This created a wound so deep he tried to escape it by lying about his age to join the army. A life of frustrated dreams compounded his trauma. He was a gifted trumpet player who had played with Hoagy Carmichael, but gave it up for a life of manual labour to support the 11 children that his wife, Ora, said just left him “plain tired”.

That hospital room confession was the key that unlocked everything. It was the first time Louie Anderson saw his father cry. As his father wept, recounting the story of his childhood, Anderson describes desperately wanting to hug him and ask why he’d never shared the story before. The moment of raw vulnerability, however, was immediately sealed over.

After apologizing for his tears, the old man defaulted to the only language of connection he had left: a gruff, deflected pride. “Did I tell you my boy is a comedian?” he asked the social worker. In that single question, a son could finally hear the validation he had spent a lifetime seeking.

Viewed this way, Louie Anderson’s choice to voice both his childhood self and his father was more than a casting decision. During every recording session, he staged a dialogue between his vulnerable younger self and his primary tormentor. By literally giving voice to his father, Anderson reclaimed him. He controlled the volume, filtering the incoherence into funny, rambling stories. He took the monster out of the closet, put a comfy jumper on him, and made him tell jokes. This whole dynamic worked thanks to Louie’s mother, Ora (voiced by Edie McClurg), Life with Louie’s calm centre whose love provided the safety net that made the anxiety bearable.

The media establishment took note of this quiet anomaly. Louie Anderson won two consecutive Daytime Emmy Awards for his dual performance. More tellingly, the series was awarded the prestigious Humanitas Prize for three consecutive years, an unprecedented achievement for a cartoon.

Interrogating the American Past

Released in 1995, the series aesthetically fit into a wave of nostalgia for a supposedly simpler post-war America. Life with Louie, however, performed a clever subversion. It used the familiar imagery of that era, defined by the clunky Rambler, the community fish fry, or the black-and-white TV, as a simplified backdrop to explore universal anxieties that are anything but simple.

The show wasn’t really about the 1960s; it was about the myth of the 1960s. It found its deepest truths in the rituals of American life by stripping them of their idealized gloss. Thanksgiving wasn’t a harmonious occasion but a pressure cooker of family grievances. A trip to the state fair became a theatre of quiet desperation, where winning a blue ribbon for the best mac and cheese dish felt like a validation of one’s entire existence.

Life with Louie‘s therapeutic subtext quietly cleared a path for a new kind of animated confessional. A direct, albeit far more profane, descendant arrived two decades later in Bill Burr’s adult animation series, F is for Family (2015-21). At their core, both shows are driven by the same engine: a comedian attempting to understand a difficult father by recreating him.

Burr’s Frank Murphy is the full-throated, R-rated evolution of Andy Anderson’s disgruntled muttering. Where Andy’s war trauma was a source of baffling non-sequiturs, Frank’s Korean War experience fuels his explosive, terrifying rants. The anxieties are the same; the volume has just been turned all the way up.

Ultimately, Life with Louie captured the uniquely American tragedy of men taught to equate love with providing, who were sent to witness the horrors of the world and then expected to return and quietly mow the lawn. It was a show that examined a flawed, difficult man and chose not to condemn him, but instead to painstakingly try to understand him.

This act of empathy, performed weekly by a son giving voice to the father who had caused him so much pain, remains one of television’s most quietly profound achievements. It suggests that the past is never truly past, but that with enough courage and artistry, it can, at the very least, be made funny.

Sometimes, for those of us looking back and trying to make sense of our ghosts, that’s close enough.