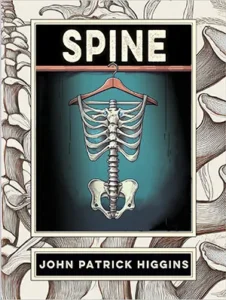

Humor writer John Patrick Higgins talks about the fading art of painful self-deprecation and other sore subjects in his new “Misery Memoir”, Spine.

Spine John Patrick Higgins Sagging Meniscus June 2025

Spine John Patrick Higgins Sagging Meniscus June 2025

Author John Patrick Higgins can’t catch a break. Unless you count the shattered bone that left him hospitalised for months in 2002. That had a lasting effect on the author of Teeth and, like Jeffrey Bernard before him, he is unwell. However, that doesn’t mean he can rest on his near-death bed. First, he had to write his new comic “Misery Memoir”, Spine. Now he’s gotta get out of bed, put some decent clothes on, sit painfully upright, and talk about the damn thing.

John, what is the worst physical pain you’ve ever felt?

Hello, Reggie. The boring answer is I broke my knee, and it was pretty sore. I did it wearing another man’s shoes, walking down three carpeted stairs, carrying a cardboard box full of aluminum stair rods. It was a spiral fracture. They happen when the bone is broken in a twisting motion, and the fracture line corkscrews through the bone. Mine was such a textbook spiral fracture that it was featured in textbooks – my right leg was published 20 years before the rest of me.

As for the pain, it was an out-of-body experience. I was beside myself, looking down on my dolphin-grey skin, buttery with sweat, my body locked, clenched. I was sure that, while the pain was white hot, a magnesium flare, the slightest movement would unleash magma-waves of agony through the rest of me. I was equally aware that searing torment was inevitable.

I wasn’t going to spend the rest of my life in the hallway of a shared flat on Coldharbour Lane. I’d be mugged, for one thing. The future would bring lifting, jostling, the shudders of a car in traffic, a breathless flight through corridors on a gurney, and all of it accompanied by nauseating fireworks of pain atomising my skeleton.

On an amusing sidenote, I was later mugged in that hallway. They knocked me spark out and stole my bagel and a cassette copy of Kate Bush’s The Whole Story.

How does that compare with the pain of writing a book? You’ve published three books in the last fourteen months. Are you compensating? Or competing?

I’m not sure writing is quite the torture writers make it out to be. No one is forcing you – certainly no one is forcing me – to do it. You could go out. Get some fresh air. Skim some stones, or whatever.

I’ve recently been writing a novel, and I’ve experienced something new and strange: I’m enjoying writing it. It’s just tumbling out, jetting out, like I’d been careless with an artery. I’m not sure that’s a good thing.

For me, a first draft usually comes quickly. The hard work is in the polishing, the tinkering, the addition and subtraction of the same comma thirty times. And it gets more complicated and difficult the more you do it. Writing becomes more like wading through whale blubber the better you get at it. You know what’s at stake. But with this book – tentatively titled The Battle of the Flowers – it’s pure ease. It feels unearned; it’s spread out ahead of me like a counterpane.

I expect there will be a price to pay. You get nothing for nothing.

As for publishing three books in fourteen months, that may seem excessive, but you must factor in the preceding fifty years, where I published precisely no books at all. Besides, there’s going to be a very long wait for the one after Spine. Now is not the time for Higgins fatigue. Pretty soon, you will be Higgins hungry again.

You wrote Spine after the success of Teeth. Did the reception of that book affect how you view your infirmity? Like the newspaper columnist, do you crane your neck looking for more injuries to talk about? Will Neck be next?

Neck is a stretch, I think.

I’m currently writing a book called Old, which should tie everything up neatly. Just being old is a pretty good Trojan horse for every anticipated malaise and impediment. I used to joke that I’d catalogue each failing body part, like a real-time flick-book of physical collapse. But this book should put to bed these morbid self-investigations.

It’s going to be a slightly different format to Teeth and Spine. Those are short and episodic, there’s a finite journey. Old is more like a guide to aging. All the stuff no one ever tells you when you’re young, all the stuff you simply wouldn’t believe when you’re young because you’re never going to get old. That’s for schmucks.

But you will get old. You will weaken, you will shrink, you will learn not to trust your body. No one will fancy you. Your hair will discolour, disappear, and reappear in places where it’s unwanted. Your friends will start to die. You’ll be irrelevant before you even open your mouth, and people will assume you’ve always been old, never imagining your storied history, the thrilling compendium of racy tales that make you up. You’re just a shrivelled mole person who can’t do a scratch card on their own because they have the wrong glasses on.

It’s very funny. It makes me so sad.

Most people try to block out or ignore pain. It is also notoriously difficult to describe to doctors. How do you focus on it and conjure ways to communicate the completely internal?

I don’t, really. The references to the actual pain are fleeting. What I’m more interested in is the sensual experience of having to do painful, boring things in dull, utilitarian rooms, with other people who don’t want to be there.

Like your yoga class.

Exactly! Old guys who turn up to the sessions in catalogue jeans and jumpers, women who quietly refuse to do any of the exercises but come back every week. I find pain quite boring because I carry it with me everywhere. It’s like an impulse tattoo I’m not keen on discussing. But the contrast between the instructor’s vital imminence and the dusty ossuary she had to work with was very funny.

Dusty Ossuary. Hell of a writer.

Indeed, Wittgenstein said we know someone is in pain not by their words but by their behaviour. Learned pain responses make the private public. What change has your discomfort made to your behaviour?

I won’t go in houses without bannisters. I’m not even flexible on this – or on anything – it’s a deal breaker. Bungalows without bannisters, maybe. On a case-by-case basis.

You write about pain in a way that’s funny. Was there ever a time you felt like language just couldn’t capture it? Or did humour succeed where screaming failed?

You’re seeing the pain through my lens. You’re seeing it at a distance. I’m removing you, very consciously, from my pain. I want you to enjoy reading about the ridiculous situations I find myself in. That’s the meat of it – you’re allowed to laugh. I point out the ludicrousness of it all. I put you at your ease. I’m not going to turn around and say, “How dare you laugh at my degradation and agony.” I’m telling you it IS funny.

Tragedy plus time is a proper rib-tickler. Otherwise, it’s just some old bloke going on about his feet, like you’ve sat next to the wrong guy on the bus.

How do you balance self-deprecating humour without turning it into self-pity? Is it a case of laughter as the best medicine?

I just write truthfully, assuming I’ll be given the benefit of the doubt. I can only write about what happened, how I, and others, felt about it then, and how I feel about it now. In retrospect, it feels like it happened to someone else, and, of course, it did happen to someone else. The events in the book battered a young, thin, dark-haired man, living in London, who had two fine, strong legs of equal length.

None of that applies to the man who wrote it. Though he’s dealing with the consequences of that bloke’s actions. Cheers, fella.

I once wrote a monologue, where a suicidal man talked and talked and talked, his logorrheic flow literally intended to talk him down from the ledge. It was staged in Northern Ireland, where there’s a crisis in men’s mental health, specifically because of men’s inability to talk, to connect, to seek help. And one of the reviews found the protagonist “whiney” and advised him to “man up”. That was a male reviewer, of course, whom I assume had been coughing and crossing and uncrossing his legs throughout the performance, irritated by the unwanted exposure to another man’s feelings.

Self-deprecation is a dying art. It used to be swift ownership of the narrative, a soft insult designed to deflect harsher brickbats. But in today’s culture of positivity and fake-it-till-you-make-it posturing, it looks like weakness and fear.

I did a gym induction – I’m not proud of it – with a woman who had no obvious sense of humour. Every time I made a funny, she would interpret it as a fear response. It was sort of fascinating. Meeting someone who can’t recognise humour and interprets it as knocking knees and raised hackles.

Of course, I might not have been very funny. See? Self-deprecating again.

Of course, the inverse of communicating pain is that other polite language game: saying you’re fine when you’re not. Fine was the title of your debut novel, in which the protagonist struggled to communicate his internal pain. How do you think these things connect in your writing?

I’m always at pains to distance myself from Paul, the protagonist of Fine, mainly because I’m aware of the overlap. He’s older than me, and he’s physically very different. He can drive a car. His legs work. He’s not me.

But there are certain people who insist that is precisely who he is. One friend, on being told every situation in the book was pure fiction, replied, “Yes, but if those things did happen, you’d do exactly what he did.” I’d written a potential autobiography, littered with speculative truths.

I’m a lot more socialised than Paul. I have friends. I have a girlfriend. I can be friendly if it’s absolutely necessary. Elderly women in doctors’ waiting rooms make a beeline for me. I give directions. And I’m not afraid to talk about how I feel.

Fine is placed squarely in the English comic novel tradition. Paul, like Bertie Wooster, is telling you everything. The reader is his trusted confidant, but his only one. Paul would never tell anyone else. He has rusty communication skills. His charm fails him. Almost every one of his social transactions ends in embarrassment or a physical altercation. I’m not kind to Paul.

I think Paul’s responses are typical and true. Men don’t want to admit to being wrong, being weak, being confused, or feeling lost or sad. They don’t want to ask for help. It’s not cool. It’s not tough. It’s vulnerable, and they’re not good at that.

I’m currently caring for my wife, who has a nerve issue that stops her from moving her arms. I have to do pretty much everything for her at the moment. It has made me keenly aware of the intimacy and isolation that come with pain. Is it the paradox of illness that it can separate us from some and bring us closer to others?

My parents would come to London from Basingstoke weekly. When I finally got out of the hospital, I recuperated in their house. They had champagne and Indian food waiting for me. My girlfriend at the time, Chloe, would cook meals for me and bring them to the hospital, because the hospital would often forget to feed me, and when they did, I couldn’t eat the food. My friend Duff travelled halfway down the country to see me. People from work trooped in looking sheepish, as I sat on my narrow bed in a big beard, and with my balls hanging out.

They very politely maintained eye contact. I mean, you certainly find out who your friends are when you’re ill.

I enjoy caring for my girlfriend, Susan, when she’s sick. There’s a dopamine smack of being aware of caring for someone. I’m not sure professional carers feel this. Caring for the sick can be like bathing a cat. But when I’m looking after her, I’m always aware of being useful, of having sudden utile value. I can fetch and carry. I can cook and shop. I can mop brows and lift people from chairs.

I don’t have any children, but it feels like I’m cosplaying as a parent. I have a charge I must look after. I’m sure I kiss foreheads and boop snoots. I think it’s quite selfish. It makes her feel better. But it makes me feel better too.

That said, I want her to be healthy for as long as possible!

Indeed, Spine has a much bigger cast than Teeth. That book was largely about the relationship that developed between you and your dentist. Spine is practically Dickensian: your parents, ex-girlfriend, your yoga class. That’s a lot! Was this a conscious decision or a consequence of the accumulative injury itself?

The first book has a small cast: the dentist, me, Susan, a few friends mentioned in passing. But that was a Marathon Man horror show: two men locked in a peculiar physical contract: one removing parts of the other’s body, the other paying him to do it.

With Spine, the story is like pinball: I’m bouncing off different groups of people all the time, I’m flitting between time periods, I’m in Cornwall, I’m in London, I’m on the Newtownards Road during rush hour. I’m Cecil B. Demoralised, orchestrating my cast of thousands with a megaphone and some whalebone stays.

I go shoe shopping, I feud with a man in an off-licence. I admire the bravery of a woman doing a backflip off a rock into the sea. The scope of the book is really twenty years. There was no way of avoiding people during all that time. Illness is often public. There are a lot of people around. There’s no velvet rope around a sick-bed.

Part of the social element of suffering is advice-giving. What is the worst piece of advice you’ve been given?

“Stop making a holy show of yourself.” I should have been making a holy show of myself all along. I was put on this earth to make a holy show of myself. Spine is a proper holy show.

Spine links current and historical pain, tying a leg injury decades ago with your present back problems – the body keeps the score. Tell us a bit about your time laid up in hospital. Do you think you could have written about the pain then? Like Proust, could you have made a legacy from being in bed? Quentin Crisp always argued his dream profession was invalid.

I didn’t write. I don’t know why. Even though I wouldn’t attempt to do any serious writing for a decade after the hospitalisation, I always had this idea of myself as a writer. In the same way Americans imagine themselves temporarily embarrassed millionaires, I considered myself a writer, though I’d never done any writing.

It was the Brett Anderson gambit: I was an author who never had an authorial experience. I have a memory – as vague as any of the rest of them – of having a typewriter in the hospital, but realistically, that can’t have happened. The best it could have been was a word processor, but who would have given me a word processor?

I didn’t write a word on the ward. In Spine, I mention I was constipated for the first nine days of my hospitalisation, something that’s common among people who’ve suffered trauma, though it’s slightly counterintuitive. In hospital, my faculties switched off one by one. I wasn’t eating. I wasn’t sleeping. I stopped reading.

It was three months in a hospice room like a Wendy House, through the burning days of summer, and I was awake for all of it. I stopped talking. The only respite was the endless operations to clean the infected plate in my leg. I fell apart. People cried when they saw me, and I cried when I saw them.

So, I didn’t write. I really wish I had. Just to track the slow inhibition of my senses. A first-hand account would have been invaluable. There’d have been a book in it.

Did being immobilised change your view on time, productivity, or the existential value of daytime TV?

I have never broken with daytime TV. It is my life, my love, my eternal muse.

You broke the leg dancing. Did it change the way you approach everyday tasks? Did you become more cautious?

I broke the ankle dancing. I broke the knee helping my girlfriend move house. I was not, on reflection, a great help. It was an altruistic act, so I should have anticipated the hefty cosmic smack-down.

The leg pain comes and goes, using a timetable known only to itself, like a window cleaner. If I don’t move, it stiffens, contracts. If I move too much, it aches and cracks and squelches. Like a cow, I can go upstairs, but coming down again is nearly impossible. I set off alarms going through customs because my right leg contains more steel than the average cutlery drawer.

Sometimes, when I’m walking down the street, I envision turning an ankle, or snapping a femur, or that my biscuit patella will crumble beneath my skin, bobbling my shins like Mrs Overall’s tights. I think about breaking my knee every day, and, you know what? I wish it had never happened.

I can’t think of any positive outcomes. Butlins doesn’t even do knobbly knee contests anymore. There’s not even a postal order in it for me.

The likes of Gene Vincent and Ian Dury made their infirmity part of their performance, however. Can you own it?

I do love the story of Gene Vincent’s manager standing in the wings while Gene’s throwing shapes on stage, yelling, “Limp harder, Gene! Limp harder!”

I mean, I’ve written two books about my massively compromised skeleton. That might be seen as “owning it”.

If Shakespeare were writing Richard III today, he might reconsider connecting monstrosity with disability. How do you avoid being bitter?

Well, he might. Caliban’s an interesting, nuanced character, a forerunner, perhaps, to the creature in Frankenstein. Dick the Shit itself is a bit of naked politicking. When you’re flattering a capricious Tudor whose claim to the throne is very shaky indeed, you go all out to make the previous incumbent look like a proper bastard. Shakespeare’s Richard had bad breath, chlamydia and wrote comments on Classic Comedy pages on Facebook about how “it’s all woke shit now lolz”. Wot a rotter.

I liked it when it was revealed Richard did have scoliosis, in the face of all the Ricardian denial. I also think it’s highly likely he did have those kids killed. But he wasn’t especially evil for an English king. They were all violent, murderous thugs. It was, sort of, the job. If someone had given him that horse at Bosworth Field, he’d probably be revered as a great and noble warrior king.

I’m not sure what I’m supposed to be bitter about. I wish I hadn’t broken my ankle, because that led to the breaking of my knee, and subsequent breaks to my ribs and my wrist. I wish I hadn’t had an infected plate in my knee, and that the attempts to rid me of infection took so long that the bones started to knit back together in the wrong shape.

But all these things happened. And it didn’t stop me doing anything I wanted to do. I had no designs on becoming a lingerie model or joining the high-kicking ladies of the Folies Bergere. The pain comes, but it often goes too. There are a great many other people worse off than me.

I’m far more bitter about my writing career. Bastards.

In this series of books, you’re very open about your health. Sadly, with age, more and more things are likely to go wrong with you. Is there any condition you wouldn’t exploit?

I will never publish a book called Colon, Reggie. Or, after the operation, Semi-Colon.