The Red Westerns made in the socialist countries of Eastern Europe appropriated the tropes of the Western to critique America’s mythologies while advancing their own.

Unlike the Spaghetti Westerns, the Red Westerns produced beyond the Iron Curtain are largely neglected by film researchers, and virtually unknown to American viewers. The East German and Romanian film industries adopted and adapted this classic American film genre to their ideological and national contexts during the Cold War.

The Westward expansion has been mythologized and dramatized in countless forms since the 19th century, from the frontier shows of Buffalo Bill through Frederick Jackson Turner’s scholarly musings on the impact of the American frontier on the national character, to the television shows and films that came to define the genre of the Western. Films like 1962’s How the West Was Won (Dirs. John Ford, Henry Hathaway, and George Marshall) and many others all rehash versions of the same story infused with American Exceptionalism: a young American nation grew organically into maturity, naturally incorporating more territories and resources in its political realm, while heroically eliminating the inconvenient Natives who stand in the path of its Manifest Destiny.

Because these narratives obscure the similarities between the growth of the US in the 19th century and the colonial exploits of, say, France or Britain, we can argue that Western movies as a genre collectively contributed to the development of national myth-making whose thrust still informs American attitudes today, in a new age of potential new territorial expansions (hello, Greenland and Canada!). In Sixguns and Society, his iconic 1977 book on the typology of the Western– this uniquely American film genre—film critic Will Wright identifies its key structural tension as the clash between the individual and society, which it shares with other foundational myths of the United States, and which may explain its enduring appeal.

This appeal was not just national. The global popularity of the Western led to various transnational adaptations throughout the 20th century and beyond, from Europe to Asia, to Latin America, which added different nuances as they engaged with the evolution of collective sensibilities around race, gender, and colonialism from different national perspectives. A less explored dimension of the international career of the Western genre is represented by its Cold War tribulations.

The term “Red Western” is used to describe those Western films produced by national media industries beyond the Iron Curtain between the 1960s and the 1980s, at the time when the appeal of Hollywood-made fare had entered a period of decline. This was an era when the new Westerns made in Italy by the three Sergios Leone, Corbucci, and Martino) became all the rage in Europe and the US, infusing new energy into the decrepit genre, and inspiring imitators elsewhere.

However, unlike the classic Westerns, which championed the pioneering spirit of the white settlers who tamed the West, or the Italian Westerns that relished in depicting the violence and corruption of frontier towns, the films made in the socialist countries of Eastern Europe used the tropes of the Western to critique America’s Exceptionalist narratives of itself and capitalism in general.

Collectively, Red Westerns illustrate the malleability of the Western genre across different ideological contexts, and its uncanny ability to maintain popular appeal. The East German and Romanian Red Westerns film industries were the most prolific in embracing the genre and because their output was widely circulated across the socialist bloc during the Cold War.

Red Westerns in the Socialist GDR

Even before Sergio Leone started the spaghetti Western craze in Italy, the Germans were at it. The first German Western ever was Der Schatz im Silbersee/The Treasure in the Silver Lake (Harald Reinl, 1962), a multilingual coproduction West Germany–Yugoslavia–France. The film was immensely successful across Europe, and spawned a series of sequels. Most of them were adaptations of the immensely popular (in Europe) novels by author Karl May (1842-1912), which portrayed the Wild West adventures of a German adventurer (Old Shatterhand) and his Apache blood brother, Winnetou.

Karl May, to this day one of the most popular German-language writers of all time, only travelled to the US long after he published his novels, so his portrayal of the Wild West was mostly informed by the his readings, and was inevitably colored by the colonial and racial assumptions of late-19th century European imperialist culture. He was also not well-seen in Eastern Germany (GDR) because he had been Adolf Hitler’s favorite author.

Consequently, when the socialist GDR film industry decided to create their own Western movies, they sought sources of inspiration elsewhere. They turned to American fiction; for example, Richard Groschopp’s Chingachgook, The Great Snake (1967) is based on James Fenimore Cooper’s 1841 novel, Deerslayer, or they created scripts loosely based on historical events, as was the case with Gottfried Kolditz’s Apachen (1973). The resulting Indianerfilme, as these East German Westerns came to be known through the German-speaking world, tended to focus far more on the plight and customs of Native Americans in the West, than on the adventures of whites seeking their fortune or the glorification of the West as site of American Exceptionalism.

East Germany’s first Western movie, Josef Mach’s The Sons of Great Bear/Die Sohne Der Grossen Bärin, was released in theaters in 1966, four years after its West German predecessor. It is based on an internationally successful multi-volume novel by German author Liselotte Welskopf-Henrich (1901-1979), who wrote the screenplay. Unlike May, Welskopf-Henrich was a communist with impeccable anti-Nazi credentials: she had been active in the resistance, helped Jews and French prisoners of war, and assisted inmates from the Sachsenhausen concentration camp outside Berlin. She was also a trained historian who had travelled to the US and Canada to research the lives of the Lakota Indians, so her portrayal of the American West and its inhabitants was better researched than May’s fanciful adventures.

Between 1964 and 1985, DEFA (short for Deutsche Film-Aktiengesellschaf, the state-owned film studio of East Germany) produced about 14 Western films, many based on Welskopf-Henrich’s books. All explicitly strove for ethnographic and historical accuracy, and emphasized the didactic role of film as a medium to educate audiences. At the same time, in their portrayal of the abuses of white settlers on the lives of the original inhabitants of the American West, the DEFA Indianerfilme promoted a message of transhistorical and transnational solidarity which built upon, and reinforced, the Cold War anti-colonial rhetoric in the Vietnam era.

The East German-depicted Native Americans were not mere symbols of the wilderness of an American West doomed by history to fade away. Nor were they embodiments of inscrutable violence as in many Hollywood Westerns, but rather individuals entitled to their culture, land, and religion who responded to the relentless encroachments of white settlement upon their lands. DEFA carefully distinguished between the various Native American tribes, creating stories that built upon historical facts.

The stories in Kolditz’s Apachen (1973) and Uzlana (1974) are told from the perspective of the Apache tribe. Other films adapted real Native American chieftains’ biographies. Konrad Petzold’s Osceola (1971) depicts the Seminole chief who freed slaves in Florida, and Hans Kratzert’s Tecumseh (1972) dramatizes the betrayal of the Shawnee chieftain at the hand of the French in the war of 1812.

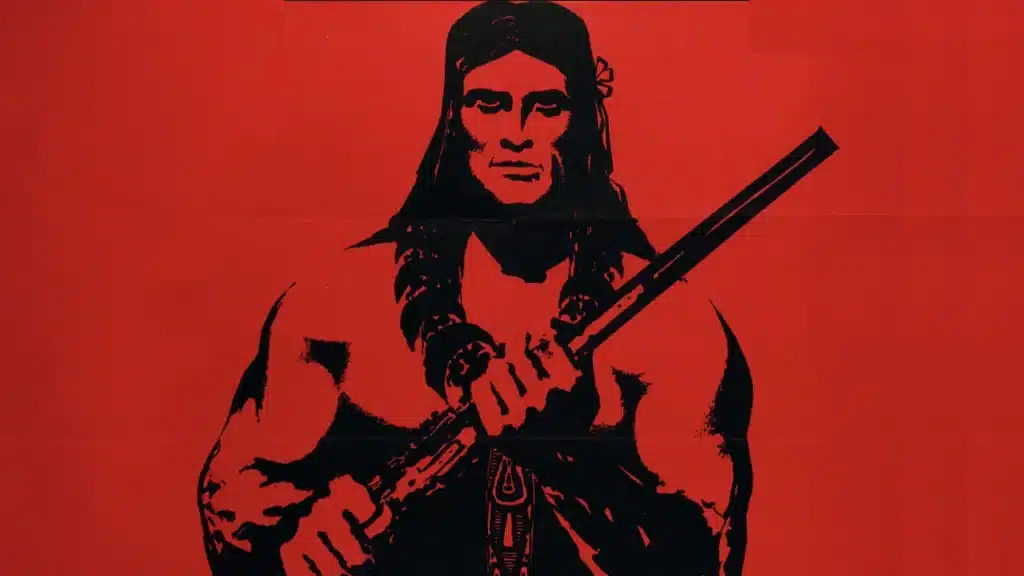

DEFA’s Native American film productions were often filmed in the same locations in Yugoslavia where the West German Winnetou films were made, and employed large, multinational and multilingual casts from across Eastern Europe. The star of all of the East German Westerns was a Yugoslav actor Gojko Mitić, who started his career as a stuntman and minor actor in the West German Winnetou films, and was propelled to stardom by DEFA’s decision to employ him as all-purpose Native chief across multiple productions.

Indeed, with his athletic physique and racially-ambiguous dark looks, Mitić became the embodiment of Native American heroism and male beauty for a whole generation of Eastern European viewers. His films were immensely popular in East Germany and circulated widely across the socialist bloc.

Overall, as film critic Gerd Gemünden notes, the distinct racial and narrative dynamics of the DEFA Westerns reflected the larger underpinnings of the socialist ideology from within which they were produced. They also allowed for a more fully researched and documented portrayal of Native American practices and history than the fantasy-infused heroism of the Karl May adaptations in the West.

Romanian’s Red Western Outlaw Margelatu

The other socialist country that produced multiple films set inspired by Western tropes during the Cold War was Romania, whose film industry in the 1980s was highly prolific. Romanian directors engaged with the Western in two different ways, both of which departed from the East German model because they remain deeply anchored in the national Romanian story.

The first model is represented by the 1980-1987 series of adventure films featuring the Wallachian outlaw Margelatu. Their plots adapt the Western format to the historical context of mid-19th century Romania, but without any overt engagement with American culture or ideology. At the center of the stories is the same charming gun-slinging, hard-drinking, philanderer and freedom-lover outlaw Margelatu, who thwarts various political plots between the Great Powers (Austria, France, the Ottoman Empire) on the territory of the then-separate states of Wallachia and Moldavia (which were to unite in 1859 as Romania).

While the plots featured various damsels in distress, corrupt politicians or police chiefs, loyal and brave sidekicks, stagecoach journeys across perilous borderlands, horse chases, and shooting matches, the series uses the Western tropes modularly and as needed. The stories are set in, and are about, Romania. The American frontier is replaced by the landscape of the fluid borderland between Orient and Occident represented by the 19th century Romanian states at the time.

The lone cowboy protagonist is Margelatu himself, an adventurer of mysterious past, whose scruffy appearance evokes Clint Eastwood’s character in Sergio Leone’s movies, with a local cultural twist: Eastwood’s iconic cigar is replaced by sunflower seeds which Margelatu constantly chomps on. This type of engagement with the format of the Western keeps its deep structure and ability for national myth-making, adapting it to a different national narrative.

The plots of Hollywood Westerns are traditionally set against the settling of the American West, and indirectly frame the modern US as an inevitable product of its earlier stages. Similarly, this series uses the format of the Western to present Romania as the product of various patriotic efforts to support the independence movement of the mid-1800s, which fed into the nationalist rhetoric of its communist regime of the 1980s.

The Transylvanian Series

The second category of Western adaptations is represented by the three-part series The Transylvanians/Ardelenii (1978-1981). These films followed the pattern set by the DEFA Indianerfilme by creating an imaginary American West, but they use it as the backdrop for stories about Romanian protagonists.

Their adaptation of the Western genre, however, is no longer modular and aesthetic, as in the case of the Margelatu series, but rather dialogic; these films directly engage with the ideological battles of the Cold War, and the key sources of humor –and cultural commentary—come from the juxtaposition of the Romanian self-image and with the image of the US. In the subtext remain the Cold War-era assumptions about the communist east and the capitalist west. As such, the films’ appropriation of the genre and its tropes overlap with the rhetoric and realities of the nationalist and isolationist regime of communist dictator Nicolae Ceausescu in the 1980s.

The trilogy opens with Dan Pita and Mircea Veroiu’s comedy, The Prophet, the Gold, and the Transylvanians (1978), followed by its sequel The Artiste, the Dollars and the Transylvanians (1980), and ends with Pita’s The Oil, the Baby and the Transylvanians (1981). Their plots are inspired by the historical wave of temporary immigration from Transylvania at the end of the 19th century, and follow the adventures of three brothers from a small village in Western Romania who are searching their fortune in the American West in the 1880s.

The cycle opens when the oldest and the youngest arrive in Utah in search of their long-lost brother, John Brad. Traian speaks only Romanian, while the youngest Romulus tries to get by with his Romanian-English dictionary, to much comic relief. The siblings are reunited, but in the process get into conflict with local villains who are abusing the communities for individual gain, a pattern which is continued in the two sequels. The happy ending of each film is reached through the collective efforts of the Romanian brothers who mobilize local ordinary people to rebel against the corrupt villains – usually local entrepreneurs, bankers, or religious figures.

Like their East German counterparts, these three films adopted some of the structural patterns of the western, particularly the fight between good and evil, the clash between individual and society, and the tension between civilization and wilderness, but with changes which fit the ideological context of 1980s Romania. They also display unique characteristics.

First, the self-serving individuals are usually negative characters; the community which, when properly organized, can defend itself from the selfish individualistic impulses of the villains. This pattern departs from that of the classical Western model where a lone cowboy rescues the community in danger from outside forces, and is intended to showcase the power of collective action over individual agency.

Second, similar to the DEFA Red Westerns, the good/evil axis does not parallel the civilization/savagery dichotomy; the Transylvanian trilogy remains overall sympathetic to the plight of the Native Americans, but the films’ main concern is to explore national mythologies and ideologies, not to educate Romanian viewers about the American West. Race is a marker of identity less crucial than ethnicity, but it serves a litmus test for assessing the American Dream.

Even the historical rivalries between Romanians and Hungarians over Transylvania become insignificant in an American setting, when only national identity seems to matter. In the last instalment of the trilogy, the Brads encounter the Orban family, Hungarian immigrants from Transylvania, with whom they first bond, then fight, and then make up and form an alliance against the local (American) villains.

The opening of The Prophet situates the Romanians within the racial hierarchies of American society, which parallels the official rhetoric throughout the communist world that targeted American racial practices and American treatment of minorities. As the Brad brothers enter the highly racialized American society, they themselves are hard to peg down by the locals, and are sometimes taken for Mexicans, other times for Natives.

Yet, they refuse to align themselves with whiteness. Instead, they befriend a freed slave and help the son of a local Native chief, adopting them both into their family, hinting again at the transnational, anti-colonial solidarity that the DEFA Indianerfilme evoked, and which dominated socialist critiques of the US.

And last, the three stories are about Romanian immigrants in America. This focus on Romanian characters interacting with American culture, mores, and space on American soil allows the trilogy simultaneously to create a successful comedy that toes the ideological line of Ceausescu’s nationalist communism, while still being subversive.

These are stories about Romanians in the West at a time when most international travel was a taboo topic in film. As it was for East Germans, emigration to Western Europe or America was impossible; Romania was a closed country, and there were very real consequences for those who tried to flee West and for the families left behind.

At any rate, in these films, America is nothing to write home about. The family patriarch, the elder brother, is supremely unimpressed by most of the iconic elements of the West: he finds American whiskey to be weak and smelly; his old flint is better than American guns, he can beat most of the tough guys in the local saloon into senselessness, and is a mean hand at poker. The stated goal of the brothers, repeated throughout the trilogy, is to return home and, by the third film, the brothers make enough money that they actually can. Their tiny Transylvanian village remains the touchstone of normality against which the three brothers measure all American customs and social practices.

Yet, the trilogy also functions as a site of resistance. Going to America does enrich the brothers, as the promise of easy gain and upward mobility embedded in the myth of the American West is not contradicted by the narrative arch of either of these films, and as such it fails to provide an effective antidote to the appeal of immigration. Above all, the films dramatize the power of free choice – the brothers have the option to go West and return home, as opposed to being forbidden to leave the country— at a time when most Romanians had very limited choices in their mobility.

TheTransylvanian series was a smashing market success for Eastern Europe. According to my research in the Romanian film archives, between the time of their release and the fall of communism in 1989, almost 18 million people watched the three films in movie theatres (in a country of 23 million), and they were widely distributed across the communist world: The Prophet was sold and screened in 14 countries (Hungary, the USSR, Lebanon, Pakistan, Syria, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, North Korea, Cuba, Egypt, East Germany, Yugoslavia, and Poland), the Artiste and the Baby in 8 (Bulgaria, Cuba, East Germany, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Syria and the USSR); all three are still regularly shown on Romanian television.

Unlike the Spaghetti Westerns, the Red Westerns produced beyond the Iron Curtain are largely neglected by film researchers, and virtually unknown to American viewers, despite the fact that rediscovering them can provide a fascinating counterpart to the American self-images and nationalist narratives about American history, which still dominate Hollywood’s output. They are also a testament to the power of the Western genre as a flexible vehicle for myth-making and fantasy which transcends the boundaries of American culture, and proves its adaptability and intelligibility in a broader global and ideological context.