With bustling filming and moments of hybrid musical lyricism, the Nasser-era Cairo Station is half neorealism and half noir melodrama.

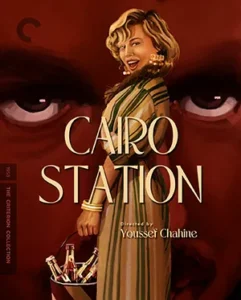

Cairo Station Youssef Chahine Criterion 12 August 2025

Cairo Station Youssef Chahine Criterion 12 August 2025

Egypt’s Youssef Chahine is among the world’s important filmmakers who remain woefully unfamiliar to audiences in Region 1, so it’s no minor event that Criterion finally brings one of his films to Blu-ray. Perhaps ironically, that film was Chahine’s most notorious failure upon its 1958 release.

Decades later, Cairo Station (Bāb al-Ḥadīd) was rehabilitated into possibly the master’s most admired classic. As Egyptian film scholar Joseph Fahim states, “Ask any Arab cinephile about the top five greatest Arab movies of all time and Cairo Station has to be in there… It was actually the biggest flop Egyptian cinema has ever witnessed.”

The title Cairo Station announces the film’s setting, where the action takes place over the course of one day. As sad-eyed old Madbouli (Hassan El Baroudi), who maintains the station’s newspaper kiosk, explains in his narration, the station sees “people from the north and the south, natives and foreigners, the rich and the poor, the employed and the unemployed.” The railway line switches that figure in the plot symbolize these promiscuous alignments and separations within one large locale of transitions.

Cairo Station, with its myriad workers and passers-through and continually arriving and departing trains, could be called the main character, although the story of Cairo Station focuses on three poor workers in a complex triangle. Chahine plays the abject Kenawi, a slouching, limping, pathetic figure who aroused such pity in Madbouli’s heart that he hired the homeless waif to assist him.

No sooner have we digested this act of charity than Madbouli visits Kenawi’s rickety wooden shelter and finds the walls pasted with cheesecake photos of scantily clad women in magazines. Madbouli’s voice-over is disturbed to realize that Kenawi is sexually frustrated.

This material already seems provocative for 1958. That’s one year before England’s Michael Powell trashed his career with Peeping Tom, which British critics found disgusting, and England was culturally far from its former “protectorate” of Egypt. Despite Egyptian cinema’s commercial fixation on belly-dancers, the industry faced serious censorship within the basically authoritarian, if dynamic, regime of President Nasser.

Like Nasser’s Egypt, the world of Cairo Station has many contradictory elements co-existing uneasily, with bold political and sexual impulses facing greedy and reactionary forces. As with Kenawi’s obsessions, women are at the center of these political and cultural storms, as old-guard patriarchs criticize modern music and unveiled wives. One surprising scene features an interview with a budding feminist group of women against marriage, although they’re as image-conscious as anyone else.

Cairo Station‘s Tangle of Desire

The shameless heroine of Cairo Station is Hanuma (Hind Rostom), one of a cadre of hussies who sell cold drinks to passengers and are constantly fleeing from police and the angry male concessioners. Hanuma is vulgar, mouthy, strong, pulchritudinous, resourceful, resilient, disrespectful, and frankly self-centered. She’s the object of Kenawi’s pathetic attentions. She mocks, teases, and makes use of him at her convenience, but she’s engaged to marry a loud, brawny porter named Abu Siri (Farid Shawqi).

Both Hanuma and Abu Siri are forces of nature, but while Hanuma is concerned only with what’s best for herself, Abu Siri is a radical trying to unionize the porters in conflict with the bully who tries to control them. Abu Siri’s political speeches and his wooing of Hanuma reinforce each other if we see Hanuma as an allegory of working-class Egypt.

Kenawi is a wild card as disturbing to their plans as the belligerent bosses. As he hears headlines about a woman found decapitated in a trunk, he crosses further into erratic behavior that signals a psychotic breakdown that will turn the plot of Cairo Station in the direction of a thriller, complete with expressive visual distortions and suspenseful twists.

According to Fahim and those who discuss Cairo Station in the Blu-ray’s extras, Egyptian audiences of 1958 had never seen such a grungy, unpredictable, sordid, working-class movie that holds up a disturbing mirror to a society that breeds discontent and hidden violence by repressing its citizens’ desires. Sexual desire becomes intertwined with economic and political freedoms in Abdel Hay Adib’s scenario, as portrayed through dialogue by Mohamed Abu Youssef.

Audiences didn’t expect Chahine to play a miserable bit of flotsam whose resonances with Sir Charles Spencer Chaplin or Raj Kapoor, “the Charlie Chaplin of Indian Cinema”, cross from the likeable to the homicidal, and in this he might have been influenced by Chaplin’s portrayal of a jolly serial killer in Monsieur Verdoux (1947). Chahine’s daring to play such a role signals his own duality as a cultural figure both revered and reviled in his country, depending on who’s doing the raving.

With bustling location filming by Alvise Orfanelli in the real Cairo Station and moments of hybrid musical lyricism by Fouad El Zahiri, the effect is half neorealism and half noir melodrama. (A bit of a spoiler: Nobody dies!) There’s even space for a rockin’ jam by a group called Mike & His Skyrockets on guitar and accordion, during which Kenawi cavorts joyfully in accord with Chahine’s love for Hollywood musicals.

Another thing audiences didn’t expect was that Shawqui, the name star known as a robust action hero, would play a political agitator who doesn’t mind beating his fiancée to teach her a lesson, which she apparently doesn’t mind learning from the big galoot as a prelude to a steamier offscreen interaction. The effect might have been comparable to buying a ticket for a Jason Statham vehicle and finding something by Eugene O’Neill, or a remake of Fritz Lang’s M (1931).

Cultural duality is embodied in the very credits of Cairo Station, with English and Arabic credits side by side. Just as Nasser’s Egypt exists at a crossroads between cosmopolitan Western modernity and Middle Eastern Islamic traditions, Chahine’s film exists at the nexus of two film posters seen in several shots. One is Niagara (1953), Henry Hathaway’s thriller of marital murder starring Marilyn Monroe. The other is Sabena, a film on which I’m unable to find information, but the poster looks like a typical ‘50s middle-class Egyptian heroine’s drama. By the way, one intriguing detail in Cairo Station‘s credits is the introduction of actor Asaad Kelada as a young boyfriend; he came to Hollywood and directed hundreds of sitcom episodes.

Fortunately, the original negatives of Cairo Station exist, and Criterion’s scan from a 4K restoration looks and sounds beautiful. So does a half-hour profile for French TV, Cairo as Seen by Chahine (1991), which attracted more controversy for its portrait of a clangorous, decaying, culturally divided city.

The Blu-ray’s extras make it clear that not only is there much more to be explored in Youssef Chahine’s output, but that Egypt’s commercial cinema has a long, fascinating history virtually unknown outside its region. It’s time for remedial classes.