Everything Is Now expertly demonstrates how NYC’s varied avant-garde subcultures were birthed in cold-water lofts, coffeehouses, and tiny storefront galleries and theaters.

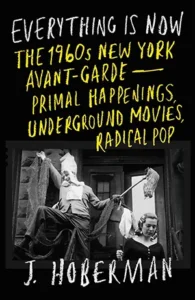

Everything Is Now J. Hoberman Verso May 202

Everything Is Now J. Hoberman Verso May 202

The New York City of the 1960s was a cauldron of avant-garde ferment and artistic innovation. The creative vitality of this era was passionately reported by the scribes of New York’s many culture weeklies, publications like The Village Voice, The East Village Other, Open City, The Paper, Cue, The New Yorker, and the deliciously titled Rat Subterranean News. Now, longtime Village Voice culture and film critic J. Hoberman has provided us with the ultimate chronicle of this still-influential explosion of creativity in Everything Is Now: The 1960s New York Avant-Garde – Primal Happening, Underground Movies, Radical Pop.

Underground film, performance, and Pop Art, experimental theater and happenings, poetry and ‘zine and comix culture, free jazz, and an edgy new brand of rock are just a few of the art forms that were being forged by a new breed of artists living in this gloriously low-rent era of Metropolis. It was a time long gone when young visionaries could survive, and indeed thrive, on ridiculously low-budget lifestyles, when they were slaves to their muses and not the unquenchable greed of landlords.

In its 400-plus pages, Hoberman expertly demonstrates how these varied subcultures were birthed in cold-water lofts, coffeehouses, and tiny storefront galleries and theaters. Ideas and expressions forged in these circumstances would coalesce into the unified “counterculture” later in the decade. It’s hard to imagine a book more densely packed with information that is so eminently readable.

“Cultural innovation comes from the margins and is essentially collective,” writes Hoberman in Everything Is Now’s introduction. “It is, to a great degree, the product of an exchange of ideas with one another. New York in the 1960s was one such cradle of artistic innovation… At heart, Everything Is Now is a tribute to those who wrote for the alternative weeklies. It is through their eyes that we might know how new work – alarming or exhilarating or both – was received.”

Hoberman takes us through the action in chapters that cover the decade year by year. He begins with a sort of pre-amble chapter, “The Connections 1958 – 60”, wherein he discusses how the Beat Generation went a little mainstream via television and some of the early stirrings that will have a larger impact as time moves on. Painter Allan Kaprow will stage the first artistic “happenings”, followed by multimedia artists Red Grooms, Jim Dine, and Carolee Schneemann.

Avant-garde filmmaker Jonas Mekas will champion emerging underground film by presenting works like Robert Frank’s Pull My Daisy and Ron Rice’s The Flower Thief, and his work as film writer for The Village Voice. As film was his critical territory as a journalist, it is Hoberman’s writing about the birth of underground movies that is most detailed and impressive. Experimental theater will begin with The Living Theater’s “jazz play” about junkie musicians, The Connection. Jazz itself will be turned on its head in 1959 with the controversial arrival of “free jazz” with Ornette Coleman’s debut at the downtown club, The Five Spot.

In 1960, loft art culture began in earnest at the 112 Chambers Street home of Yoko Ono, in the then-rundown area that would soon be known as SoHo. She will debut her “instructional art” with Kitchen Piece, where she threw leftover food from her refrigerator onto a canvas and then set it on fire. The minimalist music pioneer LaMonte Young would play a significant role in programming the events at Yoko Ono’s loft. This would include performing his own atonal pieces in partnership with John Cage, one of which would consist of the sound of a toilet flushing.

The renowned art movement FLUXUS was initiated by Lithuanian immigrant George Maciunas, who was inspired by the goings-on at Chambers Street and opened his short-lived AG Gallery. In Hoberman’s writing, young artists will “take the urban detritus for their material… in Manhattan neighborhoods that are decimated.”

The emerging coffee houses were where poetry, folk music, experimental theater, and edgy comedy thrived. The Gaslight Café, Gerde’s Folk City, Café Bizarre, Café Wah, Café A Go Go, and Mickey Ruskin’s Tenth Street Coffeehouse would go on to be the launching pads for memorable artists from folk artists Dave Van Ronk and Bob Dylan, comedians Lenny Bruce and Bill Cosby, and more outré entertainers like Tiny Tim and Moondog.

The free movement in jazz continued with the arrival of saxophone rebel Albert Ayler and drummer Bill Dixon’s October Revolution in Jazz Festival and his formation of the Jazz Composers Guild, which staged concerts by artists like Sun Ra, Cecil Taylor, Archie Shepp, and, naturally, Ornette Coleman. Hoberman writes, “free jazz was modern art, and Coleman was understood as the supreme modernist as well as the ultimate primitive of this new era.” His music was “so new that the two preeminent young reedmen, John Coltrane and Sonny Rollins, were compelled to rethink their approach.”

In another corner of music, the rock world, things began to turn seriously satirical with the arrival of The Fugs, a band of “yodeling socialists” led by author and Peace Eye bookshop owner, Ed Sanders. These political-minded pranksters took their name from Norman Mailer’s term for intercourse used in his 1948 book, The Naked and the Dead.

Naturally, Andy Warhol’s life and art are deeply detailed with his classic Pop Art pieces, his films like Blowjob (1963) and Chelsea Girls (2011), and his championing of ill-fated “it girl” actress Edie Sedgwick and the Velvet Underground. Warhol would be introduced to them at a gig at the Café Bizarre, then go on to sponsor his “Uptight” and “Exploding Plastic Inevitable” multimedia events at the old Polish theater on St. Mark’s Street, known as The DOM.

Hoberman traces the Velvet Underground’s founding to when “two stoned disciples of LaMonte Young,” John Cale and Tony Conrad, got together to rehearse with artist Walter DeMaria. He continues, their mission was to “learn an inane would-be dance-craze catalyst ‘The Ostrich.’” It was “a stoned goof on the flood of post-twist dance songs… a ridiculous novelty song” penned by none other than Lou Reed.

The beautiful cast-iron buildings of SoHo, the industrial quadrant formerly known as “Hell’s 100 Acres”, came into being as an arts hub with the founding of The Park Place Group in 1962. A group of ten painters and sculptors, led by Mark di Suvero, would rent this 8,000-square-foot site in lower Manhattan for $100 a month.

The space also housed their short-lived 10 Artists Collective Gallery. The gallery introduced the world to the cutting-edge work of these ten artists and guest exhibitors like Sol LeWitt, Eva Hesse, and Carl Andre.

FLUXUS’s founder, George Maciunas, would open 80 Wooster in 1967, the first of ten buildings, or FLUXHOUSES, that would become illegal work/live lofts for artists. At this time, these sprawling floor-through lofts could be purchased outright for $2,500; today they go for $10 million. Theater would flourish with the founding of The Wooster Group, the work of Ridiculous Theater creator Richard Foreman, and the early works of Robert Wilson, like 1968’s Baby Blood, which was staged in one of the SoHo lofts. Underground theater would go a little more mainstream with the August 1967 opening of the protest musical Hair at Joe Papp’s new Public Theater.

With the Vietnam War heating up, the art of protest became the order of the day via events like the Angry Arts Week fest in January 1967 and Yayoi Kusama’s films and performance pieces like Anatomic Explosion, an October 1968 event, which brought a group of naked dancers across from the New York Stock Exchange. The discovery of all of Kusama’s art antics of protest is a revelation in Everything Is Now.

Also making thought-provoking yet hilarious works was pioneering media prankster Joey Skaggs, who created and burned a “Vietnamese Christmas Village” in Central Park in 1969. Skaggs would also be the genius behind “The Hippie Bus Tour to Queens”. With this stunt, he took a group of East Village hippies on a tour to see the “normies” in NYC’s conservative outer borough, a parody of the then-popular bus tours of Haight-Ashbury.

One of my only wishes for Everything Is Now was to see a more thorough exploration of Skaggs’ incredible body of work, which continues today with his annual April Fool’s Day Parade in New York City. To see more on Skaggs’ life and work, watch Andrea Marini’s 2015 documentary, Art of the Prank.

The subcultures of NYC’s underground would continue to deepen and then expand, becoming a counterculture that impacted the mainstream. John Lennon and Yoko Ono would join the protest with their “War Is Over” billboard campaign, and the underground-inspired film would reach a broader audience via foreign entries like Antonioni’s Zabriskie Point (1970), the many works of Fellini, the 1967 “porn chic” of Vilgot Sjöman’s I Am Curious (Yellow), and many more.

In November 1970, Jonas Mekas would open his Anthology Film Archives as a home for bold filmmakers. Also in 1970, movie theaters like The Elgin in Chelsea would create a forum for cult movies with midnight showings of bold entries such as Alejandro Jodorowsky’s 1970 “Zen-Buddhist Western”, El Topo. His description of this outrageous film, which I have dared to see more than once, is spot-on. He labels it “a ragtag circus sideshow, replete with dwarves and amputees, wandering through a fantasy realm part Tolkien’s Middle Earth, part Wild Bunch bloodbath.”

Theater arts would cross the bridge to the Brooklyn Academy of Music. BAM would become a home for works like Robert Wilson’s The Life and Times of Sigmund Freud (1969), Deafman Glance (1970), and Einstein on the Beach (1984).

The above only begins to scratch the surface of the incredible wealth of arts and the visionary creators who enriched the world with revolutionary strides during this halcyon decade. With Everything Is Now, Hoberman has created an indispensable resource about the work they created and the lives they led which continue to resonate and influence new generations of artists in New York and cities far beyond.