Russian director Karen Shakhnazarov’s Soviet-era In the Moscow Slums and Zerograd are surreal, absurdist films rich in Impressionistic color.

In the Moscow Slums Karen Shakhnazarov Deaf Crocodile 11 February 2025

In the Moscow Slums Karen Shakhnazarov Deaf Crocodile 11 February 2025  Zerograd Karen Shakhnazarov Deaf Crocodile 11 March 2025

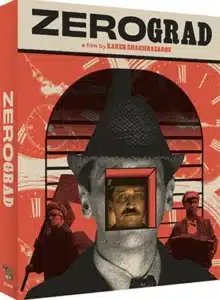

Zerograd Karen Shakhnazarov Deaf Crocodile 11 March 2025

Karen Shakhnazarov’s In the Moscow Slums (2013), a peculiar and topsy-turvy murder mystery from Russia, is based on Arthur Conan Doyle’s 1890 novel The Sign of Four but interprets its source material from an entirely separate universe. It’s a loose adaptation, as it also interpolates the works of writer Vladimir Gilyarovsky. This doesn’t exactly hijack Doyle’s original narrative, but it skews it enough so that we see how far creative liberties can stretch when they are taken with abandon.

In the Moscow Slums (its alternative title known as Khitrovka. The Sign of Four) aims, despite its bizarre leanings, for the kind of commercial accessibility that keeps afloat the many Netflix programs that have taken up the better part of America’s viewing pleasure these days. Karen Shakhnazarov keeps his mystery-caper humming with a manic energy expressed in rich Impressionistic color and a clutch of charmingly unlikable characters.

Its very Russianness adds something to the atmosphere, which seems to be reaching for the seriousness of a writer like Ivan Bunin, but often falls considerably short. What is left after the triumphs and follies of In the Moscow Slums is an enjoyably good yarn; always attractive to the eye and never too smug about its cleverness.

It is 1902 and theater actor Konstantin (played by Konstantin Kryukov) is struggling to get into his role of an impoverished youth while he rehearses for a play. His friend Vladimir (Mikhail Porechenkov, playing the author whose works partly inspired this film) is an investigative journalist, and Konstantin appeals to him for assistance in helping him develop his character.

Konstantin wants to understand the people of the slums in Moscow, so he can get a better grip on his character. Vladimir happily agrees and takes the young actor on a tour through Russia’s lower-class district. Konstantin sees an assortment of interesting people and customs. Not anticipated on the tour, however, is a murder (the victim a friend of Vladimir’s). Thus, with not too much reluctance and a little bit of verve, the two set out to unravel the mystery, which becomes increasingly complicated by the additional players who come into the fold: a villainous Englishman and his strange henchman who kills with blow-darts, and a beautiful and mysterious woman, who has some insider knowledge regarding the crime.

What follows is lively screwball fluff that takes the two men through Russia’s backroads and some very scenic routes. At times, the narrative runs at an impossible stretch, forcing the viewer to trace its labyrinthine turns in logic. Despite these frustrations, Karen Shakhnazarov maintains the interest through some truly bizarre sequences that look like an Agatha Christie play backdropped by a Willy Wonka stagecraft.

In the Moscow Slums may have done better to excise its last ten minutes that amble a little too leisurely, but Shakhnazarov brings his point home nonetheless and delivers a nicely packaged suspenser. It’s dismissive entertainment, for sure, but with some genuine allure; with maybe a few esoteric sprinklings, the main ingredient here is pure spun sugar. A simple but pleasing confection.

Gaining greater traction in the film’s crossover potential is two of the players in the principal cast: Kryukov and Anfisa Chernykh (as the beautiful, mysterious woman and Konstantin’s eventual love interest). Adding to the striking scenery (either natural or through the artifice of some exquisitely designed set pieces), these magnetic actors make the candy even sweeter for the eye.

Karen Shakhnazarov’s Cross-Section of Kafka, Agatha Christie, and Monty Python

Not nearly as flamboyant as In the Moscow Slums, but every bit as off-kilter, 1988’s Zerograd (English translation: Zero City) aims for quieter actions of screwball zaniness. The advertising blurbs for the Blu-ray (issued by Deaf Crocodile) likens Zerograd to a cross-section of Kafka, Agatha Christie, and Monty Python. Rightly so. Zerograd achieves a winning formula of all three of those influences while maintaining an identity uniquely its own. Its circular narrative refers to the nightmarish structures of Kafka’s The Castle (1926) and The Trial (1925), the distinctly political overtones assuring us that Zerograd is also a curiously playful comment on the Khrushchev Thaw that heralded a shift in the Russian arts, liberating artists and filmmakers, for a time, from Soviet rule.

Like In the Moscow Slums, Zerograd is also directed by Karen Shakhnazarov and, along with In the Moscow Slums, it sums up the filmmaker’s aesthetic. He shares similarities with fellow filmmaker Kira Muratova, a director who also made films during the Soviet rule. Both filmmakers employ an absurdist logic in their storytelling, though Muratova (a Ukrainian who made a number of films in Russia, and in the Russian language) mined a more intellectual scope concerning her dramas of the human condition.

Karen Shakhnazarov, meanwhile, seems taken with much of America’s pop-art phenomena of the 1960s. In Zerograd, Shakhnazarov explores his absurdism through an examination of rock ‘n’ roll’s effect on youth and the Soviet political agenda of the 1950s.

On a business trip as a representative for a company that sells air conditioners, Alexei Varakin (Leonid Filatov) finds himself in a strange town, and soon becomes embroiled in the surreal affairs of its inhabitants. One peculiar moment follows another: Varakin meets a receptionist who works in the nude (to the nonchalance of everyone around her), dines at a restaurant where a dessert cake is made to resemble his face, wanders through a mysterious museum in the heart of a forest, has his fortune told by a five-year-old boy, and meets a few survivors from Russia’s rock ‘n’ roll subculture of the 1950s. Throughout all this, it comes to light that Varakin’s father may have been an early co-conspirator in Russia’s emerging counterculture during the ‘50s (as a rock ‘n’ roll dancer).

Zerograd makes no pains about its themes of artistic liberation under Soviet rule. An obvious statement is made about rock music’s significance in affecting political change. Despite these apparent overtones, it never feels heavy-handed. Some fetching and deft touches keep Karen Shakhnazarov’s film an attractive watch. A charming sequence in which Varakin is led through a museum features an at once creepy and amusing array of showcases in which mannequins (in fact real people, eerily frozen in acts of play) outlines the significant markers of Russia’s history timeline. Rock ‘n Roll interludes keep the weirdness (and humor) going full speed.

Like In the Moscow Slums, Zerograd ends with some shaggy-dog meandering that circumvents the pacing and mood that the film maintains for the first three quarters of its length. It’s a misstep that slightly mars the fun, but one that seems an odd but sure signature of Karen Shakhnazarov’s narrative style.

Karen Shakhnazarov’s Two Films for Home Viewing

Deaf Crocodile delivers both In the Moscow Slums and Zerograd on Blu-ray with very clean and smooth transfers that especially show off these films’ use of color. In the Moscow Slums is bathed in sumptuous hues, with deep burgundies, emerald greens and ruby reds lushing up the frames. Zerograd is a little more subdued in its palette, but blazes vibrant and fresh in a few sequences which assures justice has been done for its restoration.

The transfer for Zerograd leans a touch soft, but it is an older film and shot on filmstock, not digital video (as is In the Moscow Slums). Audio comes through extremely well on In the Moscow Slums, and very well on Zerograd, except for a few places in which the dialogue rings just a little tinny in the beginning. This, of course, is most likely the result of the inherent technical issues of the source print. Both films are in the Russian language with English subtitles.

Both releases feature a host of supplements (interview features, video essays, a commentary track for In the Moscow Slums and an essay booklet for Zerograd) that do a deep dive into Karen Shakhnazarov’s brand of cinema. In line with Muratova and Guy Maddin, this is cinema for the curious sort.