In the late 1950s, the Cadets delivered doo-wop and R&B designed to yield pure pleasure. These Black singers’ talent and versatility keep the music fresh.

Greatest Hits The Cadets Relic

Greatest Hits The Cadets Relic

A Reason to Feel Cheerful

You’d need to have a tough heart not to appreciate doo-wop. If you have such a calcified ticker, no argument can convince you to hear the late 1950s doo-wop group the Cadets. Still, these talented, versatile singers deserve your attention, their small body of work being a reason to feel better about humanity, with its penchant for hatred, oppression, and violence, or at least to feel briefly cheerful because such entertainment exists. The Cadets made commercial music intended to bring pleasure, and most of their recordings can be appreciated purely in those terms. Of course, all their music—like any music, like any cultural artifact—needs to be seen as a product of its time and place.

Doo-wop is also known as group vocal harmony, vocal group music, or the type of music played on oldies stations that your grandfather, or even your great-grandfather, might have listened to. However, it’s unlikely that your grandmother or great-grandmother would have listened to it. An R&B subgenre, it originated in the late 1940s, gained popularity in the 1950s, and remained commercially popular until the early 1960s. Although many of the best-known doo-wop groups, such as Danny and the Juniors (“At the Hop”) and Dion and the Belmonts (“I Wonder Why”) were white, the style emerged from Black communities in US cities.

Do a Web search for the Cadets and you won’t find detailed biographies. You’ll discover that they were Black men in Los Angeles who, between 1955 and 1957, recorded covers and originals. In those years, with members dropping in and out in various recordings, the lead singers were Aaron Collins and Will “Dub” Jones, and the backups/harmonizers were Willie Davis, Austin “Ted” Taylor (replaced on at least one session by Prentice Moreland), Lloyd McGraw, and Thomas “Pete” Fox.

Their music was released by Los Angeles’ Modern Records, produced by the label’s co-owner, Joe Bihari, and arranged by Maxwell Davis. The Cadets, the same singers, also recorded simultaneously as the Jacks, with Willie Davis usually as the lead vocalist. Those recordings were released on a Modern subsidiary, RPM. Some members later performed with the Flares.

A Tribute

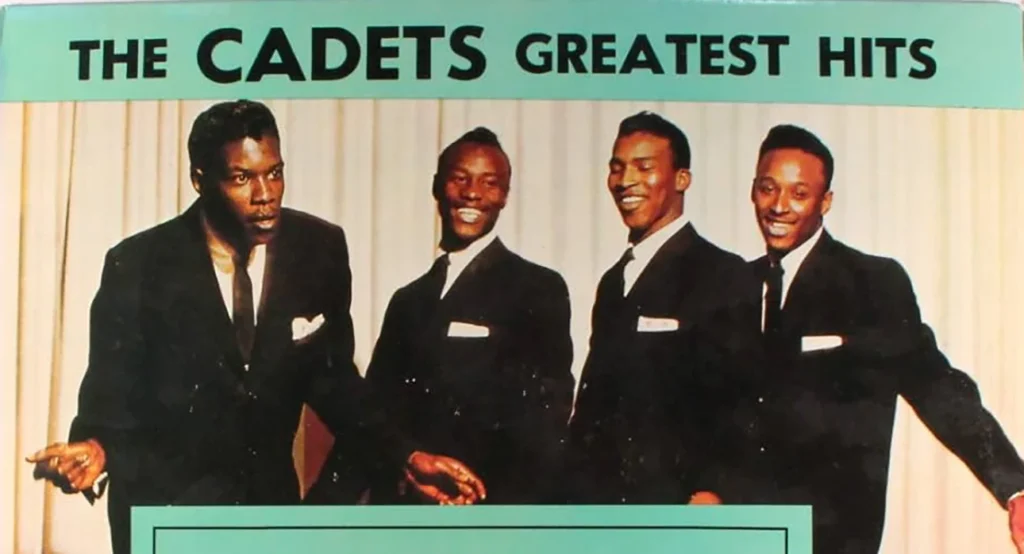

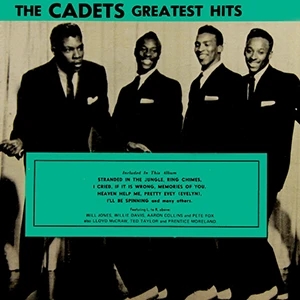

This little PopMatters tribute to the Cadets, barely skimming the surface of their story, will focus on The Cadets’ Greatest Hits, a single-LP collection put out by the reissue label Relic Records. The album was released in 19-something, sometime after 1965, but the LP doesn’t bear a date. Discogs.com shows one version with a color photo of the group on the cover, a red label, and a red-vinyl disc. A second version features the same image in black and white, a black label, and a black vinyl disc. In 2000, the UK company ABM used a different black-and-white photo and jettisoned the Greatest Hits designation in favor of just The Cadets when it reissued this material on CD.

That switch makes sense because the Relic title was inaccurate. The collection includes both hits and non-hits. Some of each, according to web accounts, were actually solo recordings made without other Cadets. Just as some Cadets collections include tracks by the Jacks and even the Flares, so this album might be more accurately titled The Best Recordings Attributed to the Cadets. Was that what Relic aimed for?

Credit the company at least with this: Unlike many reissuers of vintage recordings, they claimed to have made contact with the rights holders. A note on the back cover reads: “This LP made possible by special arrangement with Lloyd McCraw [sic] and Modern Records.”

According to Discogs, Relic, based in Hackensack, New Jersey, “was one of the first labels exclusively devoted to R&B reissues. Inspired by Irv ‘Slim’ Rose’s fabled Times Square Records, Relic was started in 1963 as a strictly 45 (seven-inch 45-rpm singles) label specializing in R&B vocal group harmony. (It wasn’t called ‘doo-wop’ until the early 1970s.) Relic’s first album, ‘Best of Acappella, Volume One’ (Relic LP 101, now reissued as Relic CD 7052), was released in February 1965.” As of this writing, Discogs indicates that Relics lasted until the late 1990s, by which time it was releasing CDs.

Consider the name: Relic. When the rock critic and performer Lenny Kaye compiled his 1972 collection of Original Artyfacts from the First Psychedelic Era, 1965‒1968, he titled it Nuggets. In other words, he considered his selections rock fragments worth preserving. Relic Records worked from a similar preservationist impulse, but their name announced a less-optimistic awareness of time’s complications. As good as pop-music nuggets may be, they still become relics.

The Relics

Fans of the late, great rock and roll band the New York Dolls will have a leg up on the Cadets’ relics. On the Dolls’ 1974 album, Too Much Too Soon, they covered the Cadets’ best-known song, “Stranded in the Jungle”. The Cadets’ version was a cover, too—a 1956 doo-wop rendering of a different doo-wop recording by the Jayhawks, which was still on the charts. That was standard practice in those days, the mid-to-late 1950s, as versions competed for attention and sales.

So, the Jayhawks released the first version of “Stranded in the Jungle”, written by Ernestine Smith and Jayhawks singer James Johnson, and the Cadets ended up scoring the bigger hit with it. There have been other versions, and in anybody’s hands it’s a comic novelty. The singer travels to Africa and ends up in a cannibal’s cooking pot. “Meanwhile, back in the States”, a rival suitor woos the singer’s woman.

In the 21st century, the scenario will likely be deemed culturally exploitative and offensive, especially in the hands of white guys such as the Dolls. But in 1956, the R&B audience, in the US, at least, seemed to understand that some Black musicians were simply having fun. Their jokes here came at other people’s expense—hey, we’re Black American singers, not African natives—but don’t take that tactic as a reason to cancel the Cadets. They had much more to offer than “Stranded in the Jungle”.

For example, “Annie Met Henry”, written by Muriel Stone and I. M. Riley, claims to tell “the story of a big romance”, but it jettisons narrative in favor of viscerally celebrating love. Annie meets Henry, they dance, and by the end of this two-and-a-half-minute number, they’re married, happily ever after. The Cadets throw themselves into pleasing you at the prospect of a perfect match. They seem to be smiling while they’re singing, and indeed while they’re swinging. The band play R&B like it’s jumping jive jazz, with full-tilt piano and sax solos churning up the rhythms.

New York Dolls took swinging lessons from these Cadets records, and on “Love Bandit”, the Cadets beat the Dolls (and so many others) to the protopunk punch. Written by Johnny Watson and Joe Josea, “Love Bandit” ignores couplehood except as the consequence of conquest. Like a proto-rapper, the lead singer smoothly positions himself as outdoing legendary outlaws such as Wyatt Earp and Jesse James. However, his only goal is one woman after another, or even many at a time.

So here again, yes, the Cadets may give offense. If you can, ignore the sexist sexual politics—the sense that women are delighted to be held captive by this irresistible bandit—and focus on the comic adrenaline. A sharp sax section keeps the energy from flagging, the singer draws out the title phrase like a kid skidding down a slide, and the backup singers delightedly ask, “Baby, baby, don’t you need somebody new? / Gonna steal your love from you.”

“Heaven Help Me”, the B-side of “Love Bandit”, written by the group’s Aaron Collins, comes from a much tenderer place, a place in the heart where doo-wop originates. That’s the significance of the nonsense syllables that gave the genre its name: expressing feelings only partly articulated by the lead singer. Here, the backups and lead achieve an angelic combination, as the group provides the pulse from which the singer’s prayer emerges. “Heaven help me / I’m in love,” he explains, with an ache that anticipates the soul giants to come in the 1960s. Just as impressive as his impassioned performance are the intertwined voices providing sympathetic support, all but saying, “Amen, brother.”

“Don’t Be Angry”, written by Rose Marie McCoy, Nappy Brown, and Fred Mendelssohn, comes from the same cloth as “Heaven Help Me”, but here the singer pleads for his beloved’s understanding. Over a jump-blues accompaniment and intermittent backing harmonies, the lead vocalist does skittering syllable runs that announce real prowess. Stay tuned for a killer and surprisingly long sax solo.

“Baby Ya Know”, written by Bob Russell and S. Roberts, packs all the group’s strengths into a declaration, “It hurt me so / To let you go”, that feels simultaneously like a lament and a release. The backup singers luxuriate in the slinky rhythm, with especially fine smooth lines and a recurring bass fillip, as the lead singer lands between Little Richard at his most soulful and Elvis Presley at his gruffest.

“Ring Chimes”, written by Bud Stockton, was the A-side, with “Baby Ya Know” as the B-side. This one opens, uncharacteristically, with percussion that could come from a folk or calypso recording, accompanied by ringing guitar accents. On top of this combination comes a complicated vocal interplay. Altogether, this celebration of church bells prefigures the quietly rocking celebrations of the transcendently commonplace that protopunk-turned-singer-songwriter Jonathan Richman has been delivering for decades.

“If It Is Wrong”, written by the Cadets’ Collins and Davis with Sam Ling, could serve as a definition of doo-wop and an explanation of what can be achieved in a three-minute pop song. Though it includes some instrumentation, you might miss everything but the opening guitar licks. Mainly, you hear plaintive lead singing and intertwined, rhythmically complicated backing vocals, combined into a heart-on-sleeve exploration of romantic love.

“So Will I”, written by George Kelly and Mayme Watts, was the A-side to which “Annie Met Henry” was the B-side. Here, the instrumentation is prominent, featuring a plinking piano that could have inspired subsequent minimalists who’ve wanted to complement their drones with simple repeating highlights. Equally worth listening to here are the lead vocalist’s finely executed excursions, which he ends by folding back into the group harmony.

“Church Bells May Ring” was written by the Willows, the doo-wop group that originally recorded it, and was at least credited to the owner of their label, Morty Craft. This track was the B-side to the Cadets’ typically gritty cover of “Heartbreak Hotel”, which is not included on this album. “Church Bells” mines the vein of “Ring Chimes”, but here an actual bell tolls for us all. Again, Jonathan Richman comes to mind as keeping alive this combination of headlong vocalizing, romantic exuberance, and devotion to the unadorned details of daily life.

“You Belong to Me”, written by the group’s Collins, the B-side to “Wiggie Waggie Woo” (which doesn’t appear on this album and is worth hearing but not essential), doesn’t radically change the group’s approach, yet it exhibits increased sophistication. Someone paid for a horn section, and the rich saxophone accents add a middle-range richness over which the lead singer glides like a bird that can stop swiftly.

“Rollin’ Stone”, written by Robert S. Riley, employs a herkily-jerkily chugging rhythm halfway between New Orleans and the Caribbean. Had Harry Belafonte rocked and rolled early in his career, he might have explored this territory. Here, as sweet as the lead vocal is (as sweet as a vocal can be while asserting that someone will “one day… be all alone”), the arresting detail is the repeating wail from one of the backup singers, like a siren announcing that the verdict is coming up.

“Dancing Dan (Sixty Minute Man)”, written by Billy Ward and Rose Ann Mark, pulls out all the stops in delivering the subtitle’s mild double entendre. Of course, when deep-voiced Dan is “blowin’ [his] top”, when he’s “rock[in’] ’em and roll[in’] ’em all night long”, when he invites you to come up and see him “if your man’s got two left feet”, he’s just dancing. The music delivers far fewer than 60 minutes, but it’s a blast of R&B, with honkin’ horns, prominent piano, and backup vocalists attesting to Dan’s prowess.

“I Cry” (here called “I Cried”, an error fixed on the ABM CD), written by Betsy Ellis, the flipside of “Don’t Be Angry”, has a pleasant groove, smooth guitar lines, and a spirited sax solo. The singer brings to mind Nat King Cole, Jackie Wilson, and Sam Cooke, while not really sounding like any of them.

Similarly, “Rum Jamaica Rum”, written by Barry De Vorzon, conjures Belafonte in general approach and spirit. It was the B-side to “Pretty Evey (Evelyn)”, also written by De Vorzon and conjuring the same island atmosphere. Though credited to Aardon [sic] Collins and the Cadets, both of these songs are reportedly solo recordings by Aaron Collins with non-Cadets.

“I Got Loaded”, written by Harrison Nelson, who recorded a 1951 hit version under his stage name, Peppermint Harris, ventures far from doo-wop, into a rollicking R&B that celebrates the deep-voiced singer’s intoxication. “Man, I sure got high”, he declares. The backup singers hum politely until they wrap up the proceedings with a fired-up “ooh-wah” or maybe even “doo-wah”, the kind of expulsion that signals free spirits at play.

“Fools Rush In”, written by Johnny Mercer and Rube Bloom, slows things down, as lead and backup singers trade lines that plead for the lover’s chance to, shall we say, fool around. On the decidedly more raucous side is “Do You Wanna Rock (Hey Little Girl)”, written by the group’s Taylor and Davis with Joe Josea. Living up to the title, the singer exhibits an abandon perhaps indebted to Little Richard.

“I’ll Be Spinning”, written by Rex Garvin, the flip side of “Fools Rush In”, delivers the sort of finely tuned harmony that inspires pop performers to create similarly layered compositions. By contrast, on “Hands Across the Table”, written by Mitchell Parish and Jean Delettre, the backup singers stay politely in the background, as the incredibly deep-voiced lead singer tingles your spine.

“Let’s Rock and Roll”, written by Joe Josea, lets it rip as the singers celebrate good times, the kind you could buy for a nickel and a dime in the late 1950s. Like the best rock and roll, this number wants to move your body as much as the singer wants to move the wearer of a red dress.

“Memories of You”, written by Andy Razaf annd Eubie Blake, traffics in the kind of nostalgia that ran through doo-wop, as though the singers had prematurely turned into codgers. Indeed, this recording features the style of crooning popular before the 1950s. Indeed, the song had been recorded by the Ink Spots in 1939. However, in their liner notes for Greatest Hits, Donn Fileti and Marv Goldberg refer to “the classic Jesse Belvin style”, referring to a now-obscure R&B singer with a mellifluous voice.

The difference in texture from other Cadets’ recordings seems to be explained by this recording’s odd history. According to various web sources, “Memories of You” originated as a Prentice Moreland solo song backed by the Cadets. However, the group’s backup work may have been replaced by another band. It seemed to have gone unreleased until it appeared on this album.

A Labor of Love

In the 21st century, countless listeners would undoubtedly hear the Cadets’ recordings as relics. But perhaps as many would render the same verdict on Nuggets, the New York Dolls, or something created last week. The good people of Relic assembled this array of diverse gems as a labor of love by doo-wop devotees for doo-wop devotees.

Perhaps they hoped that one day, in a different age, an eccentric person with a long-standing interest in recorded music, a penchant for putting recorded relics and nuggets and other fragments into contexts, and a working turntable would buy this collection for $1.50 and be inspired to spread the word or words about it to the world. Now, thanks to PopMatters, that work has been done.

Reader, is it time to rock and roll with the Cadets?

In the late 1950s, the Cadets delivered doo-wop and R&B designed to yield pure pleasure. Time has made some of their material dated or worse, but these Black singers’ talent and versatility keep the music fresh.