The violent martial arts series Warrior is supposedly a remake of Kung Fu, which conveys a strong and peaceful masculinity we sorely need in these times.

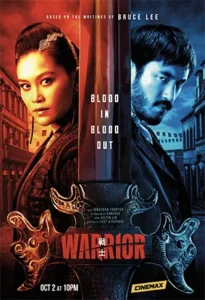

Warrior Jonathan Tropper 2019-21

Warrior Jonathan Tropper 2019-21

Imagine you’re an executive at Cinemax. Let’s say you suddenly find yourself in possession of a warehouse full of gory special effects equipment—fake severed limbs, the gear for numberless decapitation gags, and especially the mechanical and pneumatic systems that create arterial spurts. Palettes full of those. Also, there are crates full of katanas, swords, saws, and various other sharp pointy things, as well as sheets of plate glass which, if you tossed actors through them, could reasonably result in dismemberment, jugular slashings, and femoral artery severings.

“Hmm,” you think, rubbing your chin reflectively, “I wonder what sort of show we could create using the gear in this warehouse?”

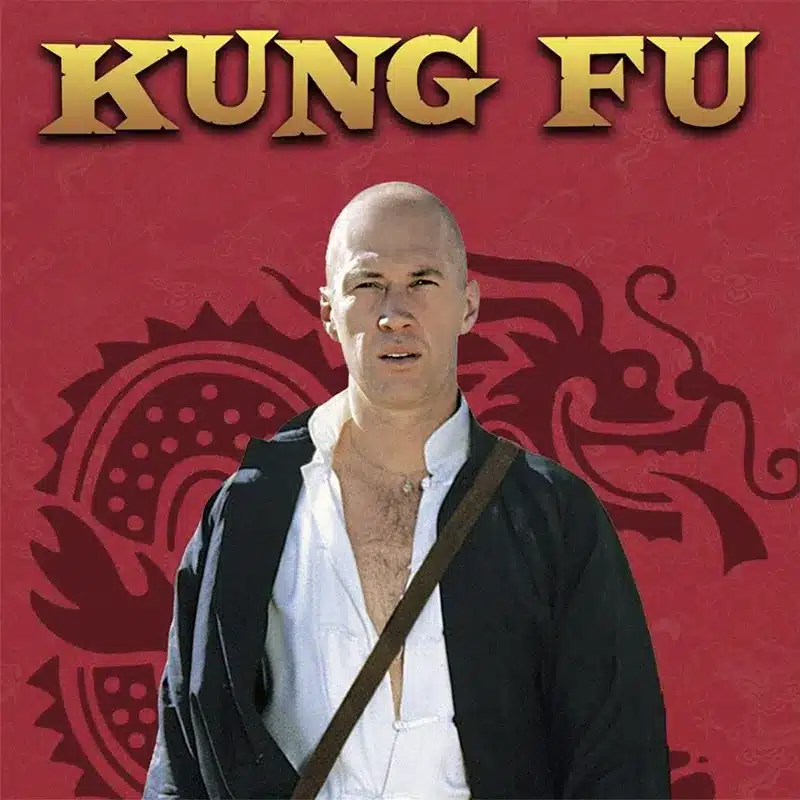

Thus, Warrior—a series executive-produced in 2019 by none other than Bruce Lee’s daughter, Shannon Lee—was born. Or maybe that’s not exactly how the series was born. Who knows? The violent martial arts series Warrior was meant to be, in Shannon Lee’s vision, a remake of the old ABC and Warner Bros. TV show, Kung Fu (created in 1972 by Ed Spielman, Jerry Thorpe, and Herman Miller). Yet Kung Fu abhors violence.

In Kung Fu, the hero, Kwai Chang Caine, played by David Carradine, is a Shaolin monk in the late 1800s who went to the pioneer West to search for his half-brother. In Warrior, the hero, Ah Sahm, played by Andrew Koji, is a Shaolin monk in the late 1800s who went to the pioneer West to search for his sister.

With Warrior, it seems that someone with clout thought it shoud be a “Kung Fu 2.0., and we’ll use all that stuff in the warehouse.” You can just hear it being pitched. A gritty, hyper-real, super-stylized version of Kung Fu, packed full of dark, moody, noirish, emo angst and orgiastic ultra-violence that makes more than ample use of the mechanical and pneumatic systems that create arterial spurts.

What made Kung Fu such a transformative show for so many people in the 1970s? Would Kung Fu‘s subversion of American notions of masculity play well in our hyper-masculinized era?

Kung Fu‘s Kwai Chang Caine detests violence and only uses his martial arts skills when forced to. Like, really forced to. The guy endures unbelievable amounts of abuse, his face a sublime mixture of tranquility and disappointment in the sorry behavior of his abusers. Finally, reluctantly, sometimes even sadly, he kicks the villain’s ass.

The sheer amount of shit Caine would take before busting out the kung fu was maddening and awe-inspiring. It was strange, intriguing. It pointed to depths of strength, real strength, that none of us had imagined, as if Gandhi had Bruce Lee martial arts skills.

In Ah Sahm (Andrew Koji), the creators of Warrior gave us one more cold, ultra-violent, hyper-masculine hero, in the vein of Jason Bourne and a hundred other adolescent-male wet-dream cartoons of strength. The creators of Warrior either did not possess enough wisdom or presumed the American public didn’t possess enough wisdom, or maybe just didn’t care either way, to notice that Kwai Chang Caine embodied more strength in his profound dislike of violence than a whole stadium full of Jason Bournes and Ah Sahms.

Kwai Chang Caine’s strength isn’t evident only in his exasperating reluctance to kick bad guys’ butts. It was obvious in his entire demeanor. His facial expressions, when he wasn’t being forced to fight sadistic cowboys, were either of serene repose, serene joy, serene compassion, or various combinations thereof.

Kung Fu Actor David Carradine was a master of these sorts of facial expressions. He had a hundred variations of serentiy. Eastern philosophy indicates that qualities like serenity, repose, joy, and compassion can only exist where fear and insecurity do not. Apparently—at least according to Warrior—those kinds of emotions could never be put into a male action hero. Deep inner tranquility, luminous kindness, quiet wonder for life? Can you even imagine it? Nah, too unmanly.

In virtually every scene in Warrior, poor Andrew Koji had to maintain a rictus of what can only be called Murderous Rage Barely Suppressed By Steely Hardened Facial Muscles. When in doubt, Murderous Rage Barely Suppressed By Steely Hardened Facial Muscles. In most scenes, his jaw muscles are clenched so hard they seemed to vibrate the ceiling joists of the super-stylized sets.

You can almost hear the director’s notes between takes: “Okay, Andrew, great stuff, but we need your brow to be way more angrily furrowed. We’re really looking for deeper, angry brow furrows. Also, we’ve noticed there are still a few neck and forehead veins that aren’t popping out and quivering the way this shot needs.”

In the rare moments Koji is not involved in interminable and numbing fight scenes, riots of arterial spurts, etc., he looks horrifically constipated, as if he’s trying to destroy his impacted fecal material with sheer hatred.

Another revolutionary aspect of Kung Fu‘s Kwai Chang Caine is that, like the teaching of Tao Te Ching, he navigates his adventures with a kind of passive flow. For the most part, things happened to Caine. This is a radical rejection of the central axiom of drama, the singular commandment of story—a protagonist with a burning desire who faces obstacles to attaining their desire.

Caine is ostensibly looking for his half-brother throughout the series. More or less. Yet, he is far from “on fire” with this goal. On most episodes, his purpose is never even mentioned. Caine is the very picture of desirelessness, non-attachment, and abiding in the bounty of the present moment. He ambles around, letting the winds of life take him where they will, stopping here and there to tranquilly regard a nuthatch or a brook.

Think for a moment about just how transgressive this peaceful warrior was for a culture steeped in feverish capitalistic avarice and manic goal acquisition. Surprisingly, the creators of Warrior actually kept this Taoist element from Kung Fu.

Just kidding. Totally joking. That’s not a thing they did.

If you ask older people about Kung Fu, those who were at least teenagers in the 1970s, you will be astonished by how many of them will say the show was formative. A surprising number, especially men—who, in their struggle to figure out what it means to be a man—describe Kung Fu as a seminal influence in their lives, which shaped them in essential ways. Despite the absurdity of David Carradine, who was in no way Asian, playing a half-Chinese character, Kung Fu was the “gateway drug” for countless people to delve into Eastern spirituality (and the martial arts). The show had that kind of gravitas.

So seriously. What on earth happened with Warrior? How could they, in their “re-envisioning” of the show, have stripped Kung Fu of nearly every quality that made it so revolutionary? Does this debasement simply reflect the ghoulish inner poverty of today’s Hollywood? Did Shannon Lee want her Kung Fu remake to be great, memorable, and even a tiny bit world-changing, but the purse-string holders constrained her creativity? Was Cinemax and then HBO simply “giving the people what they want”, meaning Warrior is just one more depressing barometer of the degenerated collective American psyche?

Maybe. However, it’s worth mentioning that, back in the early 1970s, amidst the movie blockbusters of the day, were Tom Laughlin’s 1971 martial arts/political drama Billy Jack (essentially Rambo with martial arts), Clint Eastwood’s Dirty Harry (1971), Michael Winner’s Death Wish (1974), and the detached, clinical violence of James Bond. So even then, any rational market analysis conducted by the entertainment industry would have shown an American viewing public that craved cold, macho violence. After all, people lined up and paid their hard-earned money for it.

Nevertheless, some small plucky group got it into their heads that there was also a part of people, somewhere inside them, that hungered for something higher and ennobling to the human spirit. People probably didn’t even know they longed for something higher and ennobling to the human spirit. Maybe we couldn’t know until someone dares to offer it to us. For this reason, I doubt Warrior will resonate for men in the 2020s as Kung Fu did in the 1970s.