Bruce Springsteen’s Born to Run is one of the great rock albums; it showcases youthful idealism’s shortcomings while keeping one enraptured with its false promises.

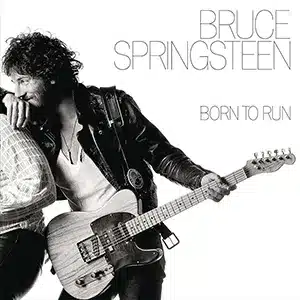

Born to Run Bruce Springsteen Columbia 25 August 1975

Born to Run Bruce Springsteen Columbia 25 August 1975

Bruce Springsteen’s make-or-break album Born to Run is a tale of resilience and hope, betrayal and perfidy—a rock and roll odyssey complete with a bloody denouement. Magic Rat, the protagonist in “Jungleland” (the last track on Born to Run), travels from New Jersey to New York City, where he ends up trapped and gunned down—dead.

At 25, Springsteen needed to write Born to Run. Of course, that can be said for every record of his; still, Born to Run is different. While his other albums came from internal and artistic struggles, Born to Run had a lot more riding on it; in fact, Springsteen’s career was on the line. His first two records—Greetings from Asbury Park, N.J., and The Wild, the Innocent & the E Street Shuffle—sold modestly; the first shifting around 22,000 units in the first year of its release. However, the prestigious label Columbia Records expected to sell a greater number and, therefore, were set to drop Springsteen if his next one was not a commercial success.

You can only imagine the pressure Springsteen felt. Yes, imagine, as most of us do not have or never had a recording contract with Columbia Records, and that we are attempting to relate to one of the most revered singer-songwriters for over half a century, whose outcome we know in advance. Besides those minor differences, Springsteen, since leaving high school, had pursued music like a religious zealot with nothing to fall back on—not even himself. Then, after releasing two albums with Columbia Records, his dreams were close to being dashed.

While many musicians would have crumbled under that amount of pressure, Springsteen confronted it head-on with an ironclad determination and delivered Born to Run. It’s a record imbued with the jouissance of 1950s rock and roll; a raw, primal energy (pure id) that, paradoxically or not, bolsters the spirituality. In other words, the spirit and the flesh commingle, as in most good rock and roll songs.

On Born to Run, Bruce Springsteen weaves the influences of Roy Orbison, Elvis Presley, and Phil Spector to produce a romantic, operatic drama played out on violent streets; a sweeping, cinematic vision of youthful escapism with perilous consequences. All of this, however, is after the fact. Therefore, Springsteen must have had reservations about the outcome: whether he got it right or wrong, created a masterpiece or not, it didn’t matter. Fate has the final word.

Speaking to Brian Hiatt of Rolling Stone in 2005, Springsteen explained, “I wanted to make the greatest rock record that I’d ever heard.” He had that kind of ambition, an ambition that drives a person to greatness or to an early grave or both. Mythologizing Springsteen as an incorrigible rock hero who went big and won implies that Born to Run’s success was driven by commerce, a proposition that is both boring and incorrect. It would still be a masterpiece—even if it had failed to sell one copy.

Understanding that Born to Run needed to be a commercial success, Springsteen could have played it safe by writing an album with a quasi-pop aesthetic. Perhaps that is easier said than done, but, undoubtedly, far easier than penning Born to Run. In fact, Springsteen composed most of the record on an Aeolian piano in a two-bedroom cottage in Long Branch, New Jersey. If this were his swansong, Springsteen would take his time: “Born to Run”, the anthemic title track, took six months to write, and it was worth every damn minute.

Born to Run was, first and foremost, about greatness. Springsteen heard greatness in Bob Dylan‘s “Like a Rolling Stone” at the age of 15; in the Beatles‘ “I Want to Hold Your Hand” in 1964; and, lastly, while watching Elvis Presley on the Ed Sullivan Show in 1957. Couldn’t he, through his own songs, bring that similar feeling of astonishment, wonder, and revelation to someone else? Yes, Born to Run had to be commercial. Yes, it had to appease the upper echelons of Columbia Records. Yet commerciality without greatness would be, at least to Springsteen, failure. Thus, he had to achieve two things: commerciality and greatness. Best-selling records are not uncommon; only Springsteen could have written Born to Run.

The Walk Before the Run

Born to Run serves as a demarcation line between Bruce Springsteen’s youthful and adult music, occupying a unique space in the songwriter’s oeuvre. Neither young nor old, cynical nor naïve, ideal nor fatalistic, Born to Run is the grandiloquent goodbye; the final revved-up roar of youthful rebellion, reverberating across lonely highways. Springsteen, thereafter, became a different writer: one who was prosaic and sparse. In fact, he would never write again with such poetic flair and élan, vision and scope.

His first album, Greetings from Asbury Park, N.J., is a solid yet misguided effort. It is the result of Springsteen, despite his desire for the album to exclusively highlight the band, compromising with John Hammond and Mike Appel, who, together, wanted the record to showcase his solo singer-songwriter material. The songs, then, range from acoustic folk ballads to R&B à la Van Morrison, as well as references to the Canadian-American five-piece the Band. Most notably, Springsteen deploys a wordiness that makes “pre-electric” Bob Dylan seem reticent.

Expectedly, Springsteen was lumped in with the “New Dylans”, a label coined by journalists who, lacking nuance and for a matter of convenience, perceived the new generation of songwriters of the early 1970s—John Prine, Elliott Murphy, and Loudon Wainwright III—as a simulacrum of Dylan (the corduroy cap-wearing and cherubic-faced troubadour Dylan, that is, not the country crooner singing of filial love as a family man in a Nashville studio).

Whether the New Dylan tag influenced Springsteen in moving away from verbosity and towards linear stories for his second album, The Wild, the Innocent & the E Street Shuffle, is debatable. For sure, though, The Wild, the Innocent & the E Street Shuffle indicates that Springsteen was far more influenced by Morrison than Dylan. For instance, Springsteen’s “4th of July, Asbury Park (Sandy)”, a paean to his adopted hometown of Asbury Park, is in the vein of Morrison’s “Cyprus Avenue”.

Furthermore, The Wild, the Innocent & the E Street Shuffle is, in terms of quality, a quantum leap forward: cohesive and ebullient; the second half of the record is a fantasy of New York City, a harbinger of Born to Run. Whereas Springsteen based his New York City stories on West Side Story (and in part Martin Scorsese), Lou Reed was influenced in part by Hubert Selby Jr.’s novel, Last Exit to Brooklyn (1964), which explains the gritty realism.

What binds the first two albums together is a vision of New Jersey or, more specifically, Asbury Park, with its eccentric monikers and local references. However, to succeed in gaining a broader appeal, Springsteen needed to universalize his stories or write a tune that resonated with millions. Either way, Springsteen achieves this on Born to Run. Springsteen’s first two albums display an inchoate greatness, punctuated by flashes of sheer brilliance and gutsy ambition, as seen in tracks like “Lost in the Flood”, “Incident on 57th Street”, and “New York City Serenade”. This greatness, that so haunted Bruce Springsteen, explodes on Born to Run.

The Fall

The élan vital of Born to Run is death. Put simply, the recognition of its own potential imminent destruction is what endows Born to Run with its tension and urgency. For instance, “born” implies a start and an end, the alpha and omega. Unsurprisingly, then, Springsteen repurposed the word “born” nine years later for his misunderstood anthem “Born in the U.S.A.”, with its suggestion of predestination, irrevocability, and finality.

The last chance feeling is the impetus of the record. “The highway’s jammed with broken heroes / On a last chance power drive,” (emphasis added) Springsteen sings in the title track “Born to Run”. Springsteen was worried that he had come to the end of the road; the literal and symbolical highway that runs through Born to Run and, generally, popular song. What is on the other side? Who knows. Springsteen just wanted to remain on the road.

Unlike the first two albums, the characters on Born to Run are not whiling away their youth on the beach; instead, they are older and working a nine-to-five job. To blow off some steam, they go racing as in “Night”, similarly to the narrator of “Racing in the Street”, three years later. Arguably, “Night” is Springsteen’s first class-conscious song.

It is in Born to Run, where Springsteen first subtly shifts the listener’s focus to the struggles of blue-collar workers, a theme that will take on greater precedence in future works and endow him with a new role: a chronicler of the working class. For now, however, it is on the periphery. As ever with Springsteen, though, the political stems from the personal. If his following two studio albums—Darkness on the Edge of Town and The River—are considered political (rightly so), Born to Run should be too.

On a biographical reading, Born to Run is about Springsteen. How can it not be? The subject of most art comes from within, and most artists fail because they cannot get outside of themselves. Yet he does not fall prey to the trap: the characters on Born to Run do not mirror its auteur; if they do, well, Springsteen biographers Dave Marsh and Peter Ames Carlin have a lot to answer for then: I have never read of Springsteen going to New York City to score a low-level drug deal, like the narrator of “Meeting Across the River”.

There has been little discourse on how the lyrics and themes of Born to Run were influenced by Bruce Springsteen; no two ways about it, he was in a state of limbo, the same as the characters. Thus, to say that the two—Springsteen and his subjects—are mutually exclusive would be misguided, if not wrong. Born to Run is inhabited by characters who are stuck and have little or no control over their existence; they are, in their eyes, born to run. Or else remain fettered in postwar suburbia. In 2012, Springsteen said at a Paris press conference, in support of his then-latest album Wrecking Ball, “I have spent my life judging the distance between American reality and the American dream.” Born to Run is the beginning.

Of course, biographical criticism can be reductive, oversimplifying, and, worse still, irrelevant. In this instance, though, a biographical reading seems reasonable in understanding the characters’ emotional states. Also, the lack of biographical reading isn’t always the case with Springsteen. For example, “The Promise”, an outtake from Darkness on the Edge of Town (1978), is often interpreted as being about Springsteen and his lawsuit with his manager, Mike Appel. Tunnel of Love, Springsteen’s 1987 album, is often referred to as his “divorce record”. Therefore, why is Born to Run not as susceptible to biographical criticism?

There are even explicit references to Springsteen, such as “Tenth Avenue Freeze-Out”, a mythopoeic retelling of Springsteen and Clarence Clemons’ meeting. In the song, the Big Man (Clarence Clemons) rescues a lonely Springsteen, who makes an appearance as Bad Scooter (after his initials, BS). Nor is Born to Run similar to Bob Dylan’s John Wesley Harding (1967), in which he deploys the Old Testament and Blakean imagery as an allegorical account of the political climate of the late 1960s. Maybe it is as simple as Born to Run being so adroitly character-driven that it belies any biographical—emotion, or otherwise—input from its creator.

Born to Run Is Unheroic

The music critic Paul Nelson, in his review of Elliott Murphy’s second album Lost Generation for Rolling Stone, writes, “If we are all, to some extent, a compilation of those whom we most admire, Murphy takes it a huge step further; he needs heroes, desires dreams, for personal and artistic sustenance.” Whereas Murphy needed heroes, Bruce Springsteen dismantles the hero archetype on Born to Run; his characters fail to emulate their heroes: “Trying to learn how to walk like heroes,” he intones in “Backstreets”.

However, it is the second part of the sentence that is most telling: “we thought we had to be”; they realize, upon reflection, that heroes are irrelevant. In other words, emulating their “heroes” will not save them from their stifling predicaments, and they cannot be their own heroes. “Well, now I’m no hero. That’s understood,” Springsteen sings in “Thunder Road”.

Whereas Murphy’s sustenance came from heroes, Springsteen, or, more accurately, his characters’ key to survival is being on the road. Although the characters do not need heroes, they need an illusion—that is to say, something to believe in—and this becomes the road. They think, with youthful desperation, that they can outrun their interpersonal and political strife by simply hopping onto a motorcycle and riding into a sunset (Wendy or Mary, beside them).

On the one hand, Born to Run represents innocence before the experience (Darkness on the Edge of Town); on the other, the fantasy that makes up so much of Born to Run shows signs of being just that: wishful thinking. As Greil Marcus writes in his Rolling Stone review, “Springsteen’s songs [Born to Run]—filled with recurring images of people stranded, huddled, scared, crying, dying—take place in the space between ‘Born to Run’ and ‘Born to Lose’.”

Although the characters have fallen for the lure of the road, they realize that it will only take them so far, as the lyrics of the title track “Born to Run” suggest. “We’re gonna get to that place / Where we really wanna go and we’ll walk in the sun / But ’til then, tramps like us.” Thus, the aim is not to run but to walk in the sun. Have the narrator and Wendy ever walked in the sun? Have any Springsteen characters?

Or is the sun a mere chimera to keep them going, pushing, pounding, like a Sisyphean figure, until the boulder rolls back and flattens them. I cannot imagine Mary and Wendy happy, Camus. Not one bit. If Born to Run was about winning, it would have failed—big time. Moreover, if Born to Run purely endorsed running, then it would have tripped on its own ideas. Heroism has nothing to do with Born to Run.

On the Road

Born to Run will perennially attract youngsters. Quite simply, it is their story: the desire to escape their hometown, not to follow in their parents’ footsteps, townsfolk, and peers. “It’s a town full of losers / I’m pulling out of here to win,” Springsteen triumphantly declares at the end of “Thunder Road”. Of course, Born to Run is a saga; thus, the album will start optimistically, and then dwindle with hope when struck by stark reality.

In any case, he is going to be a winner, and they are the losers. All fine and dandy until, after the grand piano-and-saxophone dual coda wanes, a question suddenly, if not intensely, demands to be asked: pulling out to where, exactly? To win what? Or is the escape itself the victory? That is the paradox of Born to Run: the more you peer into it, the less romantic it seems.

What is certain, though, Born to Run is a road album, in the lineage of Bob Dylan’s Highway 61 Revisited, a record inspired by Highway 61, a major highway between Wyoming (Minnesota) and New Orleans (Louisiana) extending across 1400 miles, which, during Dylan’s childhood and adolescence, ran through Duluth, his birthplace. The protean Dylan was following in the footsteps of Jack Kerouac, who emulated Woody Guthrie; in turn, Guthrie based his public image upon the figure of the hobo who, during the Great Depression, traveled across the United States via boxcars.

Popularized during the Eisenhower years, the automobile superseded boxcars, which Kerouac would nostalgically lament over as he made his cross-country road trips in an automobile with his friend Neal Cassidy, which became the basis for his roman à clef, On the Road, published in 1957. However, the tradition of traveling in literature and the arts can be traced back to European literature, writers such as Petrarch and Homer. Springsteen was not doing anything new.

On Born to Run, characters are besotted by the illusion of freedom that the road provides, whereas, to take a contemporaneous comparison, Jackson Browne’s Late for the Sky (1974) showcases the finiteness and loneliness of the road. “Tonight we’ll be free,” Springsteen intones in “Thunder Road”. Yet the narrator understands that freedom has a price: “The door’s open but the ride ain’t free.” Redemption? It’s in the hood of the car.

Certainly, the road is as shape-shifting as identity, meaning the road is where you can find or reinvent yourself, disappear and reappear; in other words, reinvent your public self, which is central to the United States’ story. However, the road can take you further away from yourself. Before long, you forget from whom or where you are running from until, in a moment of clarity, as if a revelation, it dawns on you that you are running, running, running… from yourself.

Of course, the characters never fully grasp this, as Born to Run runs at 100 mph and does not slow down; this means they are unable to conclude that the road is another trap—a mirage. By Darkness on the Edge of Town, it comes to a crashing halt: the narrator of the title track is alone on top of a hill, as this is Calvary, or Golgotha, not some sleepy suburban town, overlooking Abram’s Bridge, where his ex-wife lives. However, it isn’t all too bad for the narrator, who, though alone, has a spiritual transformation.

It is on Springsteen’s next two albums—The River and Nebraska—where things, indeed, get dark. The characters, for the most part, are isolated and lost, seeking a connection. Love or spiritual; something to kill the pain. They realize that the road can be confining, the central point of his 2019 album, Western Stars; in fact, the sequel of Born to Run, at least thematically. On Western Stars, the older, wizened characters have stayed on the road for most of their adult lives, so they know no difference; they have fallen in love with the road—even if they know it is destructive. They are the characters of Born to Run on the other side of life.

As a writer, Bruce Springsteen works in proximity to archetypal imagery; specifically, the rock and roll lexicon of cars and girls borrowed from Chuck Berry and the Beach Boys, not to mention having his own fascination with the local racing circuit in Asbury Park (he was a teenager of the 1960s, after all). By working with the cliché, Springsteen modifies and creates something new; in effect, negating the cliché. The car, then, becomes a metaphor for the characters’ spiritual journey, in which they ride to the Promised Land seeking a better tomorrow. Born to Run captures the elusive and illusive American dream.

Ascension

Bruce Springsteen saw Born to Run as a collection of vignettes taking over the course of a day. “I’d loosely imagined the Born to Run album as a series of vignettes taking place during one long summer day and night,” he writes in his 2016 memoir, Born to Run. ‘It opens with the early-morning harmonica of ‘Thunder Road’.” By the end, we are faced with a spiritual desolation in an urban wasteland: New York City, where characters seek and are denied salvation. Arguably, Catholicism has shaped Springsteen’s writing as much as the United States. In any case, he is the greatest Catholic writer in rock music; he is more preoccupied with sin than St. Augustine.

Ultimately, Born to Run is a story of going for glory and ending up with nothing. Unlike Springsteen’s characters, he would achieve his dreams. In support of the release of Born to Run, Columbia led a $250,000 campaign, which helped the record enter the top ten in its second week of release, reaching its peak position at No. 3 on the Billboard charts. A few weeks later, Springsteen graced the covers of both Newsweek and Time on 27 October.

Needless to say, Born to Run is one of the great rock and roll records; it showcases the shortcomings of youthful idealism while keeping one enraptured with its false promises. Like Jerry Lee Lewis grappling with the Holy Ghost, or Bob Dylan wrestling with the Greek muse Calliope, Born to Run finds Springsteen fighting with his genius, trying not to be destroyed by it. Moreover, there is a desperation on Born to Run that, with future records, would never be heard again. Indeed, he would get angrier: Darkness on the Edge of Town; or, darker: Nebraska. However, he would never be as existentially desperate. How could he? With Born to Run, Springsteen had been reprieved.

Overall, Born to Run is a fantasy, knowingly. However, it never glorifies the beauty and the dissolution. Born to Run tells the story of the youth, but does not restrict itself to it. Above all, it spreads the message of the value of belief—whatever that means to an individual of any age—when circumstances say otherwise. Perhaps none of us will walk in the sun. Maybe it is unattainable. Until then, though, we are born to run, happy or not.

Works Cited

Hiatt, Brian. “Bruce Springsteen on Making ‘Born to Run’: ‘We Went to Extremes‘”.

Marcus, Greil. Born to Run Review. Rolling Stone. 9 October 1975.

Nelson, Paul. Everything Is An Afterthought: The Life and Writings of Paul Nelson. Fantagraphics Books. 2011.

Phillips, Christopher, and Masur, Louis P. Talk About a Dream: The Essential Interviews of Bruce. Bloomsbury Press. 2013.

Springsteen, Bruce. Born to Run. Simon & Schuster UK. 2016.