Thirty years on, Michael Jackson’s HIStory: Past, Present and Future, Book I is among the most ambitious and personal pop statements of the 1990s, born from pressure, transformed into autobiography, and forever in our History.

HIStory: Past, Present and Future – Book I Michael Jackson Epic | MJJ 20 June 1995

HIStory: Past, Present and Future – Book I Michael Jackson Epic | MJJ 20 June 1995

In 1993, Michael Jackson was weighing his next move in the film industry. He set up a series of meetings in Los Angeles with his longtime collaborator, the Oscar‑winning producer and animator Will Vinton.

“I always thought animation would be perfect for him,” Vinton recalls. “The projects he’d tried up to that point hadn’t really worked, but he was such a brilliant talent — a natural actor, a phenomenal singer, a performer unlike anyone else. We kicked around a few ideas, but nothing seemed to click. He also had obligations to other companies that tied his hands at the time, so he wasn’t completely free.”

Those obligations were primarily to Sony. His contract called for a new record — fast. The initial plan for HIStory was a greatest‑hits package with a handful of new songs. From Sony’s perspective, that made sense: a career‑spanning celebration of Jackson’s past and stature. Jackson had no interest. “Greatest hits albums are boring to me,” he said. “I wanted to keep creating.”

Instead of a grand retrospective, he wanted a brand‑new studio album. A compromise became inevitable: a two‑disc set. The first, HIStory Begins, gathered 15 of his No. 1 hits; the second, HIStory Continues, delivered 15 new studio tracks. No one had tried that format before.

HIStory: Past, Present and Future, Book I became, without question, Michael Jackson’s most personal album. If 2011’s Moonwalk was his autobiography on paper, then 1995’s HIStory was his autobiography on record. The previous years had left an indelible mark on his spirit and his craft, and they weren’t happy chapters. Yet without that pain, we wouldn’t have songs like “Stranger in Moscow” or “Scream”.

More than a record, HIStory is a chronicle of a moment; a raw confession and, ultimately, a lesson for anyone listening. As always, Michael Jackson pushed past his own limits and refused to be boxed in. He blended genres and built an unconventional musical language. Many called the album too aggressive, too dark, the kind of reaction you’d expect from listeners who wanted him to keep serving pure entertainment. However, he wasn’t primarily an entertainer; he was an artist. With HIStory, he told his story through art.

There’s anger, suffering, disillusionment, disappointment and, in the end, optimism. “Smile though your heart is aching,” he sings on the closer, “Smile”. Yet the first music the public heard from him after the 1993/94 child molestation scandal arrived with the opening lines of “Scream”: “I’m tired of the injustice / I’m tired of the schemes.” Before that, a muffled cry swells until it shatters glass. “Don’t it make you want to scream??” he asks. It’s the perfect gateway into a work that reflects the author’s feelings during his darkest period.

“Superstars don’t make records like this,” one critic wrote of the song. “They make safe, pretty records — easy on the ear, simple, friendly… This is Michael hitting back.” Jackson never needed safe records to win an audience, and his creativity wasn’t limited. Here, he wasn’t only addressing his own experience of what he feels is an injustice; he was calling out an entire system. Near the end of the track, a newscaster’s voice breaks in: “A man was beaten to death by police after being mistakenly identified as a robbery suspect. The man was an 18‑year‑old Black male…”

In anger, Michael Jackson poses the question again, and Janet Jackson answers in the affirmative: “It makes me wanna scream.” It would be their first and only duet, though family solidarity had appeared earlier as background vocals. The “Scream” video — shot in black and white with elegant silver accents — became a 1990s sensation. With a budget of $7 million, it remains the most expensive music video ever made. More than a quarter century later, many still consider it modern by today’s standards.

Michael Jackson Self-Exiled in Moscow

Pain — that inexhaustible source of an artist’s inspiration — runs through HIStory. Listen to “Stranger in Moscow” and you’ll hear deeply personal roots. It’s a masterpiece that, paradoxically, never quite received the attention and recognition its brilliance deserved. Even so, many critics rank it among Jackson’s finest works.

It opens with rain, then a soft, mechanical pulse that melts into guitar. In the chorus, Michael keeps asking, “How does it feel?”, eventually answering: “When you’re alone / And when you’re cold inside / Like a stranger in Moscow.” He wrote it during the Dangerous tour — quite literally a stranger in Moscow at that moment — a lonely prisoner of hotel walls, standing by the window and watching the world as an outsider. The bleak, rainy Moscow winter mirrors the state of his soul. While the world seemed to turn against him and chase him down, he found himself in Russia, a country traditionally wary of the West.

“Earth Song” raises the alarm about a planet in peril and the consequences of human action. In a video filmed across four continents, we see a seal shot by a poacher, deforestation in the Amazon, dying children in Africa, and war in Croatia, among others. In a moment of anguish over the global condition, Jackson falls to his knees and digs his hands into the earth.

People around the world do the same: war victims in Croatia praying for a better tomorrow, a voodoo shaman in Africa, tribes in South America. “What have we done to the world?” he asks as he walks through a forest scorched by fire. “Look what we’ve done. What about the peace you promised your only son?” He looks back at his own state: “I used to dream / I used to glance beyond the stars / Now I don’t know where we are / But I know we’ve gone too far.”

In the final movement of “Earth Song’s” video, the film runs in reverse. The apocalyptic tableau rewinds, the earth stops shaking, the winds fall still, the animals come back to life, dolphins swim free — everything returns to its primal, natural state. It’s the last hope for a better future.

On “Money” and “D.S.”, he tells stories of greed and corruption. People are ready to do “anything for money”, even to “sell their soul to the devil.” He indicts greed and materialism, as he charges in the case of Evan Chandler, one of five parents who accused Michael Jackson of molesting their children. “They don’t care,” Jackson sings, “they’d kill for money.”

Jackson lashed out against what he called the “moral hypocrites” involved in the case against him: “You go to church / And you read the Holy Scripture / In this scheme of your life / It’s all so absurd.” For money, they will “lie, spy, kill, die…” He asks his listeners, “Are you infected with the same disease — lust, excess, greed?” and adds: “Then look at those with the biggest smile — idle schemers — because they’re the ones who’ll shoot you in the back.”

At the end of this musical confession stands “Smile”. Jackson often said it was one of his favorite songs precisely because of its message. Despite the hardships, setbacks, obstacles, and attacks, he keeps his head up and wears a smile.

Michael Jackson’s History Is One for the Books

HIStory: Past, Present and Future, Book I was first scheduled for release in late 1994, just in time for the holidays, but Michael Jackson’s relentless perfectionism forced another delay. That winter, production shifted to Los Angeles, where he continued fine-tuning the record while shaping concepts for new choreography, short films, and the album campaign.

Sony, as always, pushed for speed, and Jackson responded by working at full throttle. In the final week of recording, he told his team that sleep was no longer an option. Everything had to be ready on time.

Countless hours went into polishing the sound, mixing, and honing every detail. The crew would wrap at three or four in the morning, then start again early the next day. In the end, the hardest task was choosing the fourteen songs for the final sequence — Michael had more favorites than slots. After a five‑hour discussion, the list was finally set, and then Bernie Grundman, the mastering magician, put the finishing touches on HIStory.

The record arrived on June 16, 1995. James Hunter of Rolling Stone gave it four out of five stars, describing it as Michael Jackson’s angry reply to everything that had happened in his life to that point. The broader critical reception was largely positive. Stephen Thomas Erlewine (AllMusic) noted that HIStory Continues is the most intimate album Jackson has ever recorded. Fred Shuster (Daily News of Los Angeles) called “D.S.”, “This Time Around”, and “Money” “extraordinary slices of organic funk that will power many of the summer’s most packed dance floors.” “This Time Around” drew particular praise elsewhere, too.

The arrival of HIStory worked in two directions: as a retrospective of everything to date, and as the opening of a new chapter in which Michael Jackson — through sheer force of will — kept writing modern music history.

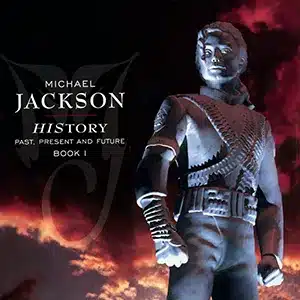

Seven‑meter‑tall statues of Michael Jackson were erected in several European cities. The album cover, with the same towering figure, spoke for itself. In a bold, superhero‑like stance, he projected strength and readiness. It was the same pose that opened the Dangerous tour. In a militaristic costume and that unmistakable posture, he looked larger than life. That was the point: to show he was stronger than ever and ready to move forward. He wanted broad attention and he got it.

For the album’s promotional short film — a cinematic realization of the album cover — Jackson tapped British director Rupert Wainwright after watching his 1994 comedy, Blank Check. The HIStory project was massive, and this video couldn’t lag behind. Budapest was chosen as the location because, as Wainwright puts it, “Budapest hadn’t been filmed that much,” and they were looking for “a fresh look and a grand stage.”

Due to tight schedules and looming deadlines, the original plan was to shoot the background plates in Hungary and have Jackson film his scenes later in New York, with everything seamlessly stitched together in post-production. At the last moment, however, he chose to fly to Budapest with his wife, Lisa Marie Presley-Jackson, determined to bring his vision to life directly on set.

The shoot, which stretched over nearly ten days, even enlisted the support of the Hungarian army. “We didn’t have any problems with them until they started to run off,” Wainwright recalls. “It was during the war in Bosnia, and the soldiers had to guard the borders. We made a deal with the Hungarians, but in the end, we didn’t pay them for that reason.”

When the army pulled out of the film project, the team chartered a flight and flew in 200 members of the British military to finish the job, a move that sent costs soaring even higher. The budget started at $2 million and quadrupled during production. Few, if any, have ever spent that much on a four‑minute promotional film.

“If you’re the biggest star on the planet,” Wainwright explains, “and you’re putting out a greatest‑hits album — sure, it could have cost less, but Michael was a true perfectionist. He saw film as part of his art.”

In the finished piece, Jackson — dressed in a silver militaristic outfit — marches with what he later called an “army of love” stretching into the distance, as ecstatic fans cheer from the sidelines. In the finale, the army unveils its gigantic statue — the very one from the album cover — at Heroes’ Square in Budapest.

Michael Jackson’s HIStory Mimicked – and Made – History

When HIStory‘s promotional film finally premiered a year later, it drew a storm of criticism. Some compared it to Triumph of the Will, the 1935 Nazi propaganda film; others claimed the martial score meant he was presenting himself as a communist leader. A third camp rejected both readings, arguing that, as a Westerner, he was positioning himself as a liberator of Eastern Europe from communism. “There was no statement in the film,” the director says. “So people naturally added falsehoods through their own opinions.”

In a single burst, Michael Jackson was branded a fascist, a communist, a pacifist, and, along the way, a megalomaniac, a narcissist, and an egotist. Those who rushed to condemn overlooked elements that point the other way. At the very start, a herald’s voice speaks in Esperanto: “We build this sculpture in the name of every nation, of global motherhood, and of the healing power of music.” The glorification of Jackson’s persona might invite charges of narcissism, but the concept itself doesn’t align with totalitarian ideologies.

Wainwright was careful not to privilege any single language. To avoid the political overtones a national tongue might carry, he deliberately turned to Esperanto. Conceived in the late 19th century as a universal language, Esperanto was a pacifist project, an attempt to ease conflicts and soften the frictions between nations. It had never before been spoken on film, making Wainwright’s choice a quiet act of pioneering.

Michael Jackson didn’t want to present himself as a political figure so much as an artist. Those who raised the statue saw him as an international figure engaged in work that unites the world and its differences. Music, in this vision, is a powerful instrument of healing that rises above divisions and disputes.

“It has nothing to do with politics, fascism, communism — at all,” Jackson told Diane Sawyer. “The symbols in the film have nothing to do with that. They’re not fascist, not dogmatic, not ideological. It’s pure, simple love. You don’t see any tanks or cannons… It’s about love. It’s art.”

The HIStory World Tour opened on September 7, 1996, in Prague, Czech Republic, before 123,000, and wrapped in Durban, South Africa, on October 15, 1997. By the end, more than 4.5 million people had seen Michael Jackson perform across 82 concerts in 58 cities, 35 countries, on five continents — making HIStory the largest tour of its time.

A core crew of 160 traveled the globe with him. In every city, another 200 workers assembled and dismantled the stage, backed by 200 local security officers. Each week of the tour, three massive stages were either being erected or dismantled. The steel frame alone weighed 200 tons and required three days to construct, with another 24 hours needed to bring it to life with lights, sound, pyrotechnics, and giant screens. In total, the three stage systems and their equipment tipped the scales at some 1,200 tons, transported across continents on 43 trucks.

The lighting was engineered to mimic daylight, a crisp 5,600 Kelvin. Fourteen technicians commanded nearly 1,000 lamps, their glow powered through some 35 kilometers of cabling that itself weighed more than 3,200 kilograms. The sound system used 150 S‑4 speakers, delivering roughly 400,000 watts and weighing 30 tons. Another 50 speakers were set up to create a sensurround effect.

Pyrotechnics were essential to the show, displaying 500 “pyro hits”. Each blast produced a detonation comparable to the TNT needed to bring down a three‑story building. At times — during “Earth Song” and “Black or White”, for instance — the stage looked demolished, though nothing was actually damaged.

Jackson also traveled with his own mobile TV setup. Four cameras followed his every move and fed two giant Jumbotrons so the crowd could see every detail onstage, no matter where they were seated. Asked what thrilled him most, production manager Chris Lamb — responsible for every facet of the biggest show on the planet — answered: “Hearing the thunder of applause on opening night, and then hearing it again and again at every show after.”

Tickets vanished at lightning speed. In Moscow, Michael Jackson shattered records once more; in Poland, Helsinki, New Zealand, Sydney, Melbourne, demand was overwhelming. The only place he chose to bypass was the continental United States, for reasons he kept to himself. The lone exception was Hawaii, where he performed for the first time. With two shows in 24 hours, he became the first artist to sell out Aloha Stadium. “I’ve never seen anything like this in Hawaii — never,” said Jim Fulton, the official promoter for Tom Moffatt Productions. In London alone, across his last three tours, more than a million people saw him — a record in itself.

Did The People of the State of California v. Michael Joe Jackson derail Michael Jackson’s career, as some biographers suggest today? At that time, he released the best‑selling double album in history and mounted a world tour that still holds records for a male artist. That’s not a career in ruins.

The accusation of pedophilia undeniably marked a turning point in his life, but not on the business side, where everything followed its natural course. The audience still craved his talent and what he did best. Was his private image damaged? When a very serious accusation is settled out of court, it can leave doubt in people’s minds. HIStory made music history, and Michael Jackson and his legacy have, no matter how we hear it, become part of our history.