I should be clear that Clint Bentley’s Train Dreams is a fine film, one of beauty, lyricism, and poignancy, boasting impeccable performances and striking imagery. It’s also a film that exists, I feel, to play at film festivals and in limited theatrical runs at boutique cinemas; one pitched exclusively at professional critics and passionate enthusiasts whose Letterboxd accounts are extensions of their very identity. It’s a film for people who pay attention to aspect ratios, not people who’re slumped on the couch after a long day’s work and want to turn their brains off for 90 minutes.

I wouldn’t bring this up, but Train Dreams is streaming on Netflix, who acquired the rights after a well-received run at the Sundance Film Festival, just in time for it to be pushed heavily during awards season. This creates, I think, a feeling of cynicism around the project that wouldn’t be there if it remained an obscure curio to be dug up only by die-hard prospectors panning for cinematic gold on the Criterion Channel (or wherever). The film has become a victim of its own success, leaping the transom from critical darling to mainstream release, and opening itself up to muddy discourse among an audience it was never targeting in the first place.

But this audience is all of us. The film, adapted from Denis Johnson’s novella by Bentley and co-writer Greg Kwedar, is about the interconnectedness of all people and all things; about the march of progress through furrows cleaved into the natural world. It’s about not just the train but the hands that laid the tracks it runs on and the trees that were felled to clear its path. It’s about dreams not as fanciful ideas but as daggers of lingering trauma and capsule love stories without end. But the all-encompassing nature of its themes doesn’t extend to its construction, which consists largely of very nice-looking golden hour landscapes and Joel Edgerton (Red Sparrow, Gringo, Dark Matter) looking pensively out of windows. His beard gets longer throughout the film, but his perspective rarely changes.

This is partly a consequence of the script’s intention to chronicle the life, from birth to death, of an everyday man who is, by definition, unremarkable. Edgerton plays Robert Grainier, a labourer who works for months at a time in the harsh forests of a rapidly changing America, lopping down trees and pounding tracks so that the burgeoning railroad can bring the country’s vast and untamed wildernesses into touching distance of each other. He is not the hero. The narrative doesn’t revolve around his axis. He is merely a bystander, someone who sees first-hand the cost of progress on an eroding natural world, but who doesn’t – can’t, really – intervene when the bill is paid in the lives of bystanders whose sacrifice is deemed worth the cost.

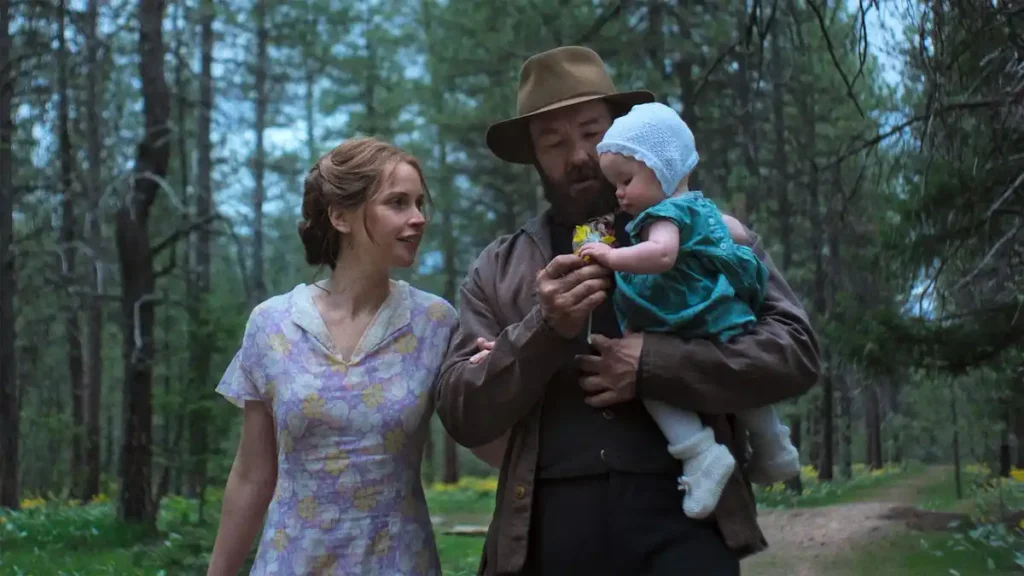

Felicity Jones and Joel Edgerton in Train Dreams | Image via Netflix

This takes many forms. The most obvious and impactful to Grainier is the senseless murder of a Chinese immigrant worker, which haunts him throughout the remainder of his life, but there are others. Grainier often meets men on the road, some he recognises from previous jobs, and they invariably die or drift away as the track extends further and further, claimed by old age or workplace accidents. These characters become the film’s tethers to reality, preventing it from becoming too dreamlike and shapeless, as award-winning slice-of-life dramas are liable to do. But Grainier doesn’t exist apart from them; he simply outlasts them, forced all the while to take in the ever-changing landscape without altering its trajectory. This is resonant, thematically. But it gives Train Dreams a glacial, shuffling pace. Its 100-minute runtime stretches into the distance like the tracks he builds.

That runtime is punctuated by the best use of voiceover narration I’ve seen in some time, the warm tones of Will Patton plugging the gaps in Grainier’s life that the film lacks time for, and contextualising the formative encounters that Grainier is too taciturn to provide his own opinions on. The narration gives the film an epic quality that its runtime and slightly recursive structure limit, but it also, at its worst, provides shortcuts to character and emotional depth that wouldn’t be there otherwise. Grainier’s relationship with Gladys (Felicity Jones; The Last Letter from Your Lover, The Midnight Sky, On the Basis of Sex) is the biggest casualty of this. Their meet-cute becomes a charming rock outline of a cabin they plan to build, and a life they plan to share, and a family they hope to raise, but each step is moved through too quickly to really resonate. William H. Macy (Ricky Stanicky), who is in the film for about five minutes, leaves a bigger imprint than Jones’s homemaker, though not, it must be said, through any fault of hers.

Train Dreams is a film of images, not words. Its most resonant one is, oddly, a pair of boots nailed to a tree, glimpsed very early and occasionally returned to, increasingly weather-beaten each time. The boots have no relevance to Grainier’s story whatsoever, which is kind of the point. They’re a story implied, a note of unexplained strangeness, their mundane nature lending their curious fate an almost mythic quality. They’re one of an infinite number of untold tales that form the basis of a world both beautiful in its ordinariness and ordinary in its beauty. Grainier is a nobody, and yet within him is contained the full breadth of human emotion. He did nothing that anybody would recognise, and yet experienced everything. As may we all.

Bentley gets this intuitively; he directs his actors to express it beautifully. Edgerton is remarkable here, delivering career-best work often in silence, his expressions rich with subtle feeling. But sometimes, especially towards the end, the imagery can become too obvious, communicating its themes too overtly, as in an older, more bearded Grainier marvelling at TV footage of nascent space exploration through a store window. The idea of a man suspended in time is less compelling to me than the idea of a man who, through his own relative unimportance, is content to be the hero in only his own story, and a fond footnote in the stories of others he met along the way.